Davey Moore: The Springfield Rifle

By Dan Cuoco

Updated: April 27, 2021

On December 15, 2020, the International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHOF) announced that Davey Moore was elected to the class of 2021 in the Old Timer Category. Later the IBHOF announced that the June induction weekend would pause for one more year while fighting Covid-19 and celebrate new inductees June 9-12, 2022. Davey’s election to the IBHOF was long overdue. He was elected to the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1986.

On December 15, 2020, the International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHOF) announced that Davey Moore was elected to the class of 2021 in the Old Timer Category. Later the IBHOF announced that the June induction weekend would pause for one more year while fighting Covid-19 and celebrate new inductees June 9-12, 2022. Davey’s election to the IBHOF was long overdue. He was elected to the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1986.

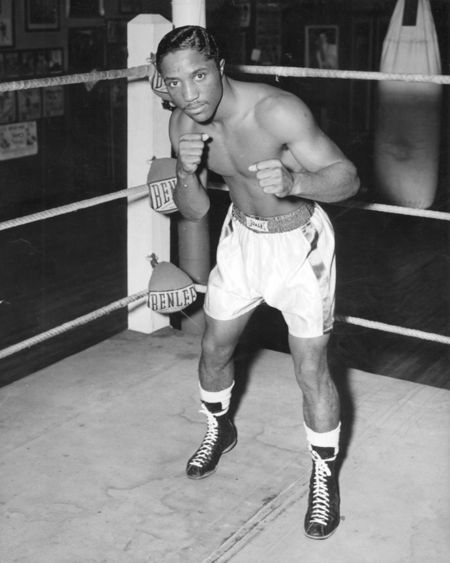

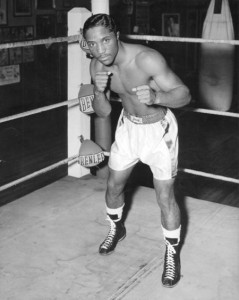

At 5 feet, 2 1/2 inches, and hindered by short arms, Davey Moore adopted a style to overcome these deficits. His aggressive counter-attack, which featured an excellent left jab, ripping body punches, and effective pin-point counter-punching, made him one of the most dangerous pound-for-pound fighters competing in the 1950s and early 1960s. Tracy Callis describes Davey “as a boxer with plenty of tools – ‘savvy,’ natural fighting skills, punching power and courage; He gave it his all and let it all hang out.”

Davey Moore was born in Lexington, Kentucky, on November 1, 1933, the youngest of seven brothers and two sisters. His father, Reverend Howard T. Moore, a local Minister, moved his large family to Springfield, Ohio in 1934 when he was appointed pastor of a small church in Urbana, OH. The City of Urbana is located in West Central Ohio, 16 miles north of Springfield, Ohio.

As a schoolboy, Davey got into many street fights that did not sit well with his father, a strict disciplinarian. No matter how hard his father punished him, Davey continued to get into street fights. Eventually, by age 14, Davey started to outgrow street-fighting and was influenced by five of his brothers who boxed as amateurs and became interested in amateur boxing. Davey left Springfield’s Keifer Junior High School at age 14 to compete as an amateur. Faking his age at 16, the legal minimum, he engaged in 120 amateur bouts, losing five.

Davey won four Regional Golden Gloves titles before winning the National AAU bantamweight title in Boston in April 1952 with a first-round knockout over Chocken Maekawa of Honolulu. He followed this impressive victory in June 1952 by earning a berth on the U.S. Olympic team. In the finals of the Olympic Trails held in Kansas City, MO., Davey won the 119-pound weight class trials with a third-round stoppage of Frank Echavarria of Blackfoot, Idaho.

Davey competed in the 1952 Olympics Games held in Helsinki, Finland. The other team members included: Ed Sanders, Heavyweight (Gold Medalist); Norvel Lee, Light Heavyweight (Gold Medalist); Floyd Patterson, Middleweight, (Gold Medalist); Ellsworth Webb, Light Middleweight; Louis Gage, Welterweight; Charles Adkins, Light Welterweight (Gold Medalist); Robert Bickle, Lightweight; Edson Brown, Featherweight; and Nate Brooks, Flyweight (Gold Medalist). Davey drew a bye in the first round, decisioned Egon Schidan of Germany in the second round, and lost a close decision to Korean Joon Ho Kang in the quarter-final round. According to the Associated Press, “Moore was nipped by Joon Ho Kang of Korea in a close tussle that he could have won had he been more aggressive.” A disappointed Moore headed home to ponder his future. With few prospects open to him other than boxing, he decided to turn professional.

Davey made his professional debut on May 11, 1953, in Portsmouth, OH, winning a unanimous six-round decision over Willie Reece. Both fighters were making their professional debuts and fought six two-minute rounds. He scored five more victories (three by kayo). He was named Ring Magazine’s Featherweight Prospect of the Month before losing a hotly disputed six-round decision to the more experienced Russ Tague, 24-1-2 (16) in Chicago, IL on October 3, 1953. Tague, who had been fighting professionally for three years, was dropped in the second round by a left hook to the body followed by a terrific right cross to the chin for a nine-count. Moore continued to punish Tague in the third with jolting lefts and rights. Both boys slugged it out for the remainder of the bout with the fans in an uproar. The decision in Tague’s favor was unpopular.

Less than three weeks later, Moore was involved in a bizarre ending in his first eight-rounder at Municipal Stadium in Grand Rapids, MI. Davey knocked opponent Paul Prado of Detroit through loose ring ropes in the third round. Prado injured his back when he fell through the ropes, and 67-year-old Municipal Stadium employee Bill Butler was knocked out when he was struck on the head by a loose ring post while helping to tighten the ropes. The ringside officials declared the bout “no contest.” Ring Magazine’s editor Nat Fleischer called the decision unjust, stating “the bout belongs to Moore by a knockout.” The Michigan Athletic Board of Control upheld the referee’s decision.

Davey stopped his next two opponents before dropping another hotly disputed decision, this time to former world-ranked featherweight contender Jackie Blair, 71-24-8 (36), in his first ten-round main event. The first four rounds found Moore hitting Blair with many hard lefts and rights forcing Blair to clinch and hold on. In the fifth, Blair began to outbox Moore with long left jabs. The sixth followed the same pattern, with Blair scoring with his educated left hand. The seventh heat produced many thrills as the crowd stood and cheered for the full three minutes as both fighters stung each other. In the eighth, ninth, and tenth, Davey was all over Blair scoring with stiff left hooks to the body as Blair desperately tried to keep Moore at bay. The bout ended with both slugging toe-to-toe amid cheers from the crowd. The decision in Blair’s favor was unpopular.

Davey resumed his winning ways with three straight knockout victories improving his record to 12-2-0-1 (8) before engaging in his next big test against former featherweight title challenger Charley Riley, 66-27-1 (37) in Riley’s hometown of St. Louis. According to the Associated Press, the hard-punching Riley dropped Davey for an automatic eight count with a right in the seventh, but Davey evened the score, dropping Riley in the ninth. Davey walked away with a majority decision, 52-48, 51-49, 50-50.

Controversy dogged Davey again in his next fight against Pittsburgh’s Herky Kaminsky in Springfield, OH. He floored Kaminsky in the third and fifth rounds (the bell saving Kaminsky in the fifth). When the fight was over the contest was ruled a draw. When Davey’s manager Ted Ordanik learned that only one judge and the referee Tony Zale scored the fight, he filed a protest. Two judges had been scheduled to work the fight, and officials said they did not know what happened to the other judge. The protest was denied. A month later, Davey won a convincing decision over Kaminsky in a rematch. He finished 1954 on a high note with a knockout victory over Dick Armstrong in Dayton, OH. On December 7th, he stopped Cincinnati’s Eddie Burgin in the ninth round to win the Ohio State featherweight title.

In 1955 Davey was forced to take fights on the road because of the lack of featherweight action in most parts of the United States and also because rival managers were starting to avoid him as an opponent for their own fighters. They began calling him the “Springfield Rifle” because he hit so hard. Feeling his managerial team didn’t have the right connections to move him towards championship contention, he signed on with veteran fight manager Willie Ketchum who had handled Solly Krieger, Lew Jenkins, Lou Salica and Jimmy Carter.

In May 1955, Davey traveled to Panama for a two-fight series. In his first fight under Ketchum, he took on Isidro Martinez, 12-2-0 (6), Panama’s number one contender for the national crown. Moore dropped Martinez twice in the fourth round but was dropped himself in the ninth round en route to losing a controversial decision. Ring Magazine’s Panama correspondent Juan W. Copeland stated, “If Martinez had gotten a draw every fan in the house would have been satisfied.” Two weeks later Davey took on tough, hard-hitting Pedro Tesis, 18-2-0 (7), the reigning Panamanian featherweight titleholder. Tesis had handed Isidro Martinez his only two professional losses in Panamanian national title fights (W TKO 15 and W PTS 15). Despite suffering a flash knockdown in the fourth round, Davey walked off with a popular decision. Two months later, Davey traveled to Cuba, where he dropped a unanimous decision in Havana to hard-punching Santiago Martinez, 17-3-1 (12). The loss dropped his record to 17-3-1-1 (10).

Back in the United States, road warrior Moore handed hard-punching lightweight Ray Riojas, 14-0-1 (10) his first professional defeat in El Paso, TX; knocked out Nat Jackson, 22-9-0 (10) in two rounds in New Orleans; and finished the year with a sixth-round disqualification win over Philadelphia’s Jimmy Hackney, 16-4-0 (7), in his New York debut at Madison Square Garden. Fighting in the semi-final eight on the undercard of Ludwig Lightburn-Ralph Dupas, Referee George Walsh disqualified Hackney for “not fighting.” Ironically, this would be the only time Davey would ever fight in New York. The fact that he was never given a chance to headline a fight in Madison Square Garden bothered Davey throughout his career.

1956 was a bad year for Davey. He suddenly had difficulty getting fights. He would only fight three times that year. Davey stated in an interview that whenever his name came up, the usual comment from managers was, “What are we going to gain by getting our brains bashed in? No big dough and no name. Fight him… for what?” With a wife and children to consider, he quit the ring and went to work for International Harvester and later worked construction, operating a jackhammer. Davey had met his future wife, Geraldine Welch, in 1949. She was 16, and Davey was 18. They dated for three years and married in 1952. (Davey and Geraldine were later blessed with five children: Denise, born in 1953; Ricky, born in 1955; Dave Junior, born in 1958; Lynise, born in 1960; and Davia, born in 1961). The three fights he did engage in that year were a fourth-round knockout victory over journeyman Charlie Slaughter in Montreal, Canada on June 5, 1956; a six-round decision over journeyman Jimmy DeMura in Chicago on October 10, 1956; and an eight-round loss by decision to 20-year-old up and coming Bobby Rogers on November 7, 1956. Davey, who had ended 1955 looking like a promising star on the rise, ended 1956 looking like an ordinary fighter. But, things were about to change.

Whatever hard-luck Davey encountered in 1956 turned completely around in 1957, starting with an upset decision over Ring Magazine’s seventh-ranked Gil Cadilli on April 10, 1957, at Biscayne Arena in Miami, FL. The United Press reported: “Davey Moore blasted his way into the boxing limelight tonight with a unanimous decision over Gil Cadilli. ….. Moore crashed punches of every sort into the taller Cadilli from the first round on and had control of the fight all the way. Cadilli, the favorite at fight time because of his greater speed, proved no faster than the broad-chested Ohio fighter, but the Los Angeles man showed 1,018 ringside fans he could take hard punches and fight back. ….. Moore making his first television appearance was bleeding from a cut over his left eye and another on his left cheek but did not seem the least bit tired at the end of the bout. …. Moore seemed to gain strength as the fight went on and slugged harder every time Cadilli’s fist caught him. At the end of the bout, Moore was pounding Cadilli almost at will.”

Davey first entered Ring Magazine’s world ratings at number 6 with a sensational ten-around upset victory over Panama’s featherweight champion, Isidro Martinez, 18-3-1 (6) at The Capitol Arena Washington, DC. The Associated Press reported: “Moore, an 8-5 underdog made the odds appear ludicrous as he battered the Panamanian featherweight champion from start to finish. Davey slashed across a sizzling right in the seventh that sent Martinez to the canvas. Isidro was up at the count of 2, but even after waiting out the compulsory toll of 8, was a wobbly warrior. Moore lost to Martinez in Colon, Panama two years ago. Moore stated after the fight, “I beat Martinez in Panama two years ago, but they gave him the duke – naturally, the fight taking place in his own hometown of Colon. Since then, I had been anxious to get Martinez in the ring again and even matters with him. It was a long chase, but I finally evened the score with him.”

Davey first entered Ring Magazine’s world ratings at number 6 with a sensational ten-around upset victory over Panama’s featherweight champion, Isidro Martinez, 18-3-1 (6) at The Capitol Arena Washington, DC. The Associated Press reported: “Moore, an 8-5 underdog made the odds appear ludicrous as he battered the Panamanian featherweight champion from start to finish. Davey slashed across a sizzling right in the seventh that sent Martinez to the canvas. Isidro was up at the count of 2, but even after waiting out the compulsory toll of 8, was a wobbly warrior. Moore lost to Martinez in Colon, Panama two years ago. Moore stated after the fight, “I beat Martinez in Panama two years ago, but they gave him the duke – naturally, the fight taking place in his own hometown of Colon. Since then, I had been anxious to get Martinez in the ring again and even matters with him. It was a long chase, but I finally evened the score with him.”

A month later, Moore won a split decision over Mexican featherweight champion Victor Manuel Quijano, 36-8-2 (11) at the Syracuse War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse, NY. Although the decision was split, the referee and one of the judges had Davey winning comfortably. Davey continued his winning streak through the end of 1957 and 1958 with victories over Jose Luis Cotero, 34-13-5, (W PTS 10) in Washington, DC, Victor Manuel Quiano, 38-9-2, (W TKO 9) in Los Angeles, Fili Nava, 45-12-2, (W PTS 10) in Los Angeles, Vince Delgado, 14-4-2, (W KO 3) in Los Angeles, Roberto Garcia, 24-4-2, (W PTS 10) in Mexico City, Mexico; Lauro Salas, 74-44-10, (W PTS 10) in Los Angeles, Kid Anahuac, 39-13-5, twice (W PTS 10) in Tijuana, Mexico and Los Angeles, and Ricardo (Pajarito) Moreno, 31-4-1 (31 KOs), (W KO 1) in Los Angeles, CA.

By the time he met Moreno, Davey was the number one ranked featherweight in the world by both Ring Magazine and the National Boxing Association. His record stood at 34-5-1-1 (14). The Los Angeles Times reported: “The winner of this bout, had been promised a World Featherweight title shot against Hogan (Kid) Bassey. Moreno had already lost a title bid with Bassey, by 3rd round kayo, earlier in the year. Moore was the #1 ranked contender by the NBA entering the bout. Moreno began the fight cautiously, staying away from Moore. A minute into the fight, Moore landed a short straight right, which dropped Moreno, who arose without a count. Two minutes into the round, following a good hook by Moore, Moreno landed his best punch of the bout, when he let go a powerful left hook, which sent Moore five feet across the ring, against the ropes. Moreno closed in, wildly, but was quickly tied up by Moore, who waited for referee George Latka’s break. Moore proceeded to dance away, and then landed a long left hook which floored Moreno for a second time. At the count of three, Moreno removed his mouthpiece, and placed it alongside himself. Though it appeared he may have been taking advantage of the count, to rise later, Moreno did not move, and was counted out, holding his body partially up with his left elbow. The time of the knockout was 2:58. Boos greeted Moreno from the fans at the completion of the ten count, many of whom came out to watch him fight.“

By the time he met Moreno, Davey was the number one ranked featherweight in the world by both Ring Magazine and the National Boxing Association. His record stood at 34-5-1-1 (14). The Los Angeles Times reported: “The winner of this bout, had been promised a World Featherweight title shot against Hogan (Kid) Bassey. Moreno had already lost a title bid with Bassey, by 3rd round kayo, earlier in the year. Moore was the #1 ranked contender by the NBA entering the bout. Moreno began the fight cautiously, staying away from Moore. A minute into the fight, Moore landed a short straight right, which dropped Moreno, who arose without a count. Two minutes into the round, following a good hook by Moore, Moreno landed his best punch of the bout, when he let go a powerful left hook, which sent Moore five feet across the ring, against the ropes. Moreno closed in, wildly, but was quickly tied up by Moore, who waited for referee George Latka’s break. Moore proceeded to dance away, and then landed a long left hook which floored Moreno for a second time. At the count of three, Moreno removed his mouthpiece, and placed it alongside himself. Though it appeared he may have been taking advantage of the count, to rise later, Moreno did not move, and was counted out, holding his body partially up with his left elbow. The time of the knockout was 2:58. Boos greeted Moreno from the fans at the completion of the ten count, many of whom came out to watch him fight.“

On March 18, 1959, 25-year-old Davey Moore entered the Olympic Arena in Los Angeles to fight for the featherweight championship of the world. His opponent, highly regarded world champion Hogan (Kid) Bassey, 59-11-2 (30), was 26-years-old and in the prime of his career. He won the vacant world title in an elimination tournament on June 24, 1957, in Paris, France with a tenth-round stoppage of Cherif Hamia. This was his second title defense. On April 1, 1958 he had knocked out Ricardo (Pajarito) Moreno at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles in the third round. In the early rounds of their title fight it looked like Bassey would have an easy time with Davey. After an even first round, Bassey stung and hurt Davey in the second and third rounds. There was little to choose between both fighters in the fourth and fifth rounds. Moore took command of the fight, starting with the sixth round. He landed a flurry of lefts and rights to the head and body that appeared to have Bassey on the verge of a knockout. His sharp-shooting tactics, ripping body punches, and effective counter-punching completely outclassed Bassey in every aspect during the last seven rounds of the fight. Davey had Bassey bleeding above both eyes and continued to pile up points. Bassey, to his credit, never gave up and tried in vain to land his vaunted power punches. But Moore’s sharp punches to the head and ripping body punches were too much for the champion. After the thirteenth round, with Bassey well behind on points and nasty cuts above both eyes, his manager George Biddles refused to send him out for the fourteenth round.

On March 18, 1959, 25-year-old Davey Moore entered the Olympic Arena in Los Angeles to fight for the featherweight championship of the world. His opponent, highly regarded world champion Hogan (Kid) Bassey, 59-11-2 (30), was 26-years-old and in the prime of his career. He won the vacant world title in an elimination tournament on June 24, 1957, in Paris, France with a tenth-round stoppage of Cherif Hamia. This was his second title defense. On April 1, 1958 he had knocked out Ricardo (Pajarito) Moreno at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles in the third round. In the early rounds of their title fight it looked like Bassey would have an easy time with Davey. After an even first round, Bassey stung and hurt Davey in the second and third rounds. There was little to choose between both fighters in the fourth and fifth rounds. Moore took command of the fight, starting with the sixth round. He landed a flurry of lefts and rights to the head and body that appeared to have Bassey on the verge of a knockout. His sharp-shooting tactics, ripping body punches, and effective counter-punching completely outclassed Bassey in every aspect during the last seven rounds of the fight. Davey had Bassey bleeding above both eyes and continued to pile up points. Bassey, to his credit, never gave up and tried in vain to land his vaunted power punches. But Moore’s sharp punches to the head and ripping body punches were too much for the champion. After the thirteenth round, with Bassey well behind on points and nasty cuts above both eyes, his manager George Biddles refused to send him out for the fourteenth round.

Under California rules, Davey Moore was declared champion by thirteenth-round knockout. At the time of the stoppage, Davey was ahead on points. Referee Tommy Hart and Judge Mushy Callahan scored it 126-119, while Judge George Latka had it 125-121 for Moore. Most newspapers had Moore well ahead. Veteran Ring Magazine boxing correspondent Bill Miller, who covered boxing in California and had personally witnessed all the top talent in the featherweight division, stated after the fight: “In usurping Hogan Bassey’s crown, he didn’t by any means show the skill and hitting power of Willie Pep or Sandy Saddler. But no formidable opponent looms, not even Bassey, unless he can solve the counter punching ability of Moore, who is likely to dethrone the new champ in the near future. His counter punching is his best asset, and it is that which put the skids under Bassey.”

Bassey had a return clause that called for a return engagement within ninety days. But because of the cuts, the return was pushed back to August. On August 19, 1958, Davey Moore made the first defense of his world title against Bassey in a highly anticipated rematch.

Moore bulled Bassey in the clinches, took his best punches, and then waded in again. Although Bassey was outpunched by the counter-punching champion in the early rounds, he managed to rock Moore in the fourth round by a looping left to the head and in the fifth round by a stiff right to the head followed by a series of lefts and rights to the head. Moore appeared fully recovered when he came out for the sixth round; however, he regained command by staggering the challenger with a left to the head. Moore showed coolness and confidence all the way and grew stronger as the fight wore on. He used his speedy left hook mainly to the head. That swift left hook eventually cut and closed Bassey’s right eye. The cuts near the right eye started bleeding freely as the fight progressed. Bassey opened the tenth round strongly, but it was his last gasp. He scored with a right and a telling left to Moore’s head shortly after the bell, and the champion appeared to give ground. But Moore was only biding his time. He charged suddenly and pounded Bassey with rights and lefts to the head as he chased him around the ring. Bassey tried to cover up, showing only his elbows to the relentless champion, but Moore broke through his guard with a left to the mouth. Bassey tried to clinch, but Moore had him backing up and on the ropes as the round ended. Bassey was unable to answer the bell for the eleventh round. His right eye was closed, and the cuts near his eye were bleeding freely. Moore was ahead on all scorecards, Judge Charley Randolph, 98-91; Judge Joey Olmos, 98-94; and Referee Frankie Van, 95-93. The UPI had the champion ahead, 97-93.

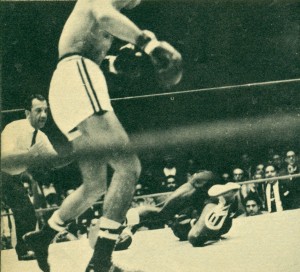

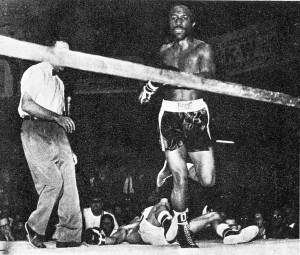

On October 20, 1959, Davey traveled to London to take on British featherweight champion Bobby Neill, 25-3-0 (21) at Wembley Stadium. Neill and his managers were hoping that a victory over the champion would lead to a title fight. Unfortunately for Neill and his backers, the cold-as-ice champion put an end to that dream in a mere 2 minutes and 55 seconds of the first round. Looking every bit like the finest fighter pound-per-pound in boxing, Moore dropped the outclassed Neill four times before the referee stopped the fight. Neill didn’t have a chance, and everyone in the crowd of 11,000 knew it. British correspondent Johhny Sharpe reported: “It was a pity that the fans could not have seen more of the combination punches and moves that give credit to a real world’s champion. Moore in his latest outings had stopped Hogan Bassey twice, and in doing so made the little Nigerian cry ‘Enough’ twice.” Davey ended 1959 by defeating tough lightweight Hilario Morales, 24-3-1 (16), in San Francisco. Moore dropped Morales in the first round en route to a dominating ten round decision.

On October 20, 1959, Davey traveled to London to take on British featherweight champion Bobby Neill, 25-3-0 (21) at Wembley Stadium. Neill and his managers were hoping that a victory over the champion would lead to a title fight. Unfortunately for Neill and his backers, the cold-as-ice champion put an end to that dream in a mere 2 minutes and 55 seconds of the first round. Looking every bit like the finest fighter pound-per-pound in boxing, Moore dropped the outclassed Neill four times before the referee stopped the fight. Neill didn’t have a chance, and everyone in the crowd of 11,000 knew it. British correspondent Johhny Sharpe reported: “It was a pity that the fans could not have seen more of the combination punches and moves that give credit to a real world’s champion. Moore in his latest outings had stopped Hogan Bassey twice, and in doing so made the little Nigerian cry ‘Enough’ twice.” Davey ended 1959 by defeating tough lightweight Hilario Morales, 24-3-1 (16), in San Francisco. Moore dropped Morales in the first round en route to a dominating ten round decision.

In early February 1960, Davey headed to Venezuela for a series of non-title fights. On February 22nd, he stopped number three world-ranked contender Sergio Caprari, 47-2-1 (17), of Italy in eight rounds. Davey had Caprari down in the fourth, seventh, and eighth rounds before the fight was stopped. This was Caprari’s first loss by stoppage.

Disaster befell Davey in his second fight in Venezuela on March 14, 1960, when 20-year-old Venezuelan power puncher Carlos Hernandez, 12-0-2 (10), stopped him in seven rounds. Davey suffered a broken jaw and was dropped three times before the pain forced him to retire at the end of the seventh. The Associated Press reported: “Hernandez dropped Moore in the third round for a six count and fractured his jaw. Moore appeared to be stumbling backward when the blow was delivered. Moore also went down for counts in the fourth and seventh rounds. But Davey, dead game, suffered the tormenting pain through the seventh, taking a brutal beating all the way. Finally as the round ended, he could stand it no longer and signaled to the referee to stop the fight.” After the fight Moore’s manager, Willie Ketchum, said, “Davey was tagged as he was pulling away – the angle of the punch busted his jaw. It was just a bad break.” This fight put Hernandez in the boxing public eye, where he would remain throughout his career. He would later go on to win the World Junior Welterweight Title from hall-of-famer Eddie Perkins in 1965. Besides his knockout of Davey Moore, Hernandez would go on to knock out or stop hall-of-famer Joe Brown, former lightweight champion Carlos Teo Cruz, top contenders Kenny Lane, Paolo Rosi, Bunny Grant, L.C. Morgan, Tito Marshall, Baby Vasquez, Percy Hayles, Alfredo Urbina, and defeat Len Matthews, Doug Vaillant, Gil Cadilli and Angel Robinson Garcia among others.

Disaster befell Davey in his second fight in Venezuela on March 14, 1960, when 20-year-old Venezuelan power puncher Carlos Hernandez, 12-0-2 (10), stopped him in seven rounds. Davey suffered a broken jaw and was dropped three times before the pain forced him to retire at the end of the seventh. The Associated Press reported: “Hernandez dropped Moore in the third round for a six count and fractured his jaw. Moore appeared to be stumbling backward when the blow was delivered. Moore also went down for counts in the fourth and seventh rounds. But Davey, dead game, suffered the tormenting pain through the seventh, taking a brutal beating all the way. Finally as the round ended, he could stand it no longer and signaled to the referee to stop the fight.” After the fight Moore’s manager, Willie Ketchum, said, “Davey was tagged as he was pulling away – the angle of the punch busted his jaw. It was just a bad break.” This fight put Hernandez in the boxing public eye, where he would remain throughout his career. He would later go on to win the World Junior Welterweight Title from hall-of-famer Eddie Perkins in 1965. Besides his knockout of Davey Moore, Hernandez would go on to knock out or stop hall-of-famer Joe Brown, former lightweight champion Carlos Teo Cruz, top contenders Kenny Lane, Paolo Rosi, Bunny Grant, L.C. Morgan, Tito Marshall, Baby Vasquez, Percy Hayles, Alfredo Urbina, and defeat Len Matthews, Doug Vaillant, Gil Cadilli and Angel Robinson Garcia among others.

Davey was out of action for four months before returning to the ring on July 20, 1960 to face Frank Valdez in Albuquerque, NM. During his four months of inactivity many questions lingered in the boxing fraternity. “If his jaw heals properly-as it should-and if he recovers from the shock-as he should-Davey can resume his career with little more than a bad memory and a hospital bill to show for one harrowing night in Caracas. But-and it could be a tragic but-if physical complications set in, or if Davey’s morale fibre proves permanently damaged, then the 27-year-old champion may find his future behind him.”

Davey helped to dispel those questions when he stopped Valdez, 18-4-3 (9), the reigning Texas State featherweight champion in the sixth round. Moore drilled Valdez to the canvas twice in the sixth before the referee halted proceedings. Two weeks later Davey was in Tijuana, Mexico for a tune up fight with young local hotshot Kid Iraputo, 18-5-3 (5). The Kid gave him a good ten round workout in preparation for his upcoming title defense against Japanese featherweight champion Kazuo Takayama in Tokyo, Japan. Davey won by unanimous decision.

Against the ninth-ranked Takayama, 36-11-9 (9), Davey proved that his broken jaw had completely healed and that he hadn’t lost a thing during his convalescence. Moore, making his debut in the Orient, carried the fight to the challenger from the opening bell but could not floor him, although his stiff jolts to the body had Kazuo gasping and holding on time and time again. Many in the vast stadium, including Moore, thought the fight was stopped in the thirteenth round when Referee Jimmy Wilson appeared to stop the fight as Davey was belting away with both hands with Takayama trapped against the ropes and led him to his corner. Wilson said he heard the bell ring ending the round. Neither fighter had heard it. Davey finished strongly as he continued to weave under the jabs of his 23-year-old long armed challenger and slash away at his mid-section and head with both hands. Takayama used every ounce of effort he had to stay on his feet. Moore retained his title with scores of 74-62, 73-64, and 73-66.

Moore continued his busy schedule with knockout victories over David Camacho, 18-22-1, in Nogales, Mexico, and Rudy Corona, 23-9-0, in Ciudad, Mexico to finish 1960.

Davey started 1961 off in early January with a European tour. First up was number one ranked featherweight contender (Ring Magazine and the National Boxing Association) Gracieux Lamperti, 46-7-2 (22), in Paris, France. Davey’s name and fame guaranteed a full house at the Palais des Sports. Veteran European Ring Magazine boxing correspondent Charlie Parrish reported: “Both fighters weighed over the featherweight limit with Lamperti some three pounds heavier. Moore proved to be a non-stop battler in the Henry Armstrong style and Lamperti fought at top speed to hold off the American’s attacks. In the third round, Moore swiped the Corsican with a sizzling left hook to the jaw that dumped Gracieux on the deck for ‘9’ but the European champion appeared unshaken by the knockdown and fought back in short bursts of in-fighting that made Moore give ground. Lamperti fought well in the fourth, dropping Moore for an instant in the fifth and in the sixth round he slammed over a left hook that brought Moore to the deck for a count of ‘3’. Possibly nursing his chin, lately broken during his South American sojourn, Moore let up somewhat for the rest of the round. In the final stages of the fight Moore staged a tremendous rally which Lamperti weathered without undue difficulty but which sufficed to guarantee Moore the decision.”

Moore continued his European tour with victories over former lightweight contender Fred Galiana, 114-16-13 (65), in Madrid, Spain (W TKO 4) and unbeaten Italian featherweight champion Raimondo Nobile, 24-0-2 (5), (W PTS 10) in Rome, Italy before heading home for his third title defense against Danny Valdez in Los Angeles.

When Davey got back to the States and started to prepare for his title defense against Valdes, two reporters asked him why he travels so much. His answer was simple, “money.” He said he fights the countries best right in their own backyard and is rewarded handsomely for the risks. His manager Willie Ketchum echoed Davey, “We go where the dough is. In boxing, you only got a few years to make it. Guys in other professions have forty or fifty years. We got only one-fourth or one-fifth that time.”

Davey’s next challenger was 21-year-old Los Angeles featherweight Danny Valdez, 17-5-0 (8), ranked number three by the National Boxing Association and number seven by Ring Magazine. Valdez had rocketed into the top ten with two victories over number one ranked featherweight contender Ricardo Gonzales, 94-5-7 (50), (W PTS 10, W TKO 5), and Boots Monroe (W KO 1) for the California State featherweight title. Danny and his managerial team thought they were ready to take on the champion. Danny stated before the fight, “Ingemar Johansson only had 21 fights when he won the title from Patterson. Emile Griffith just took the title from Paret with only 24 fights. Everything has been speeded up these days-why, not fighters?”

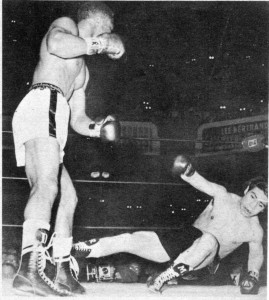

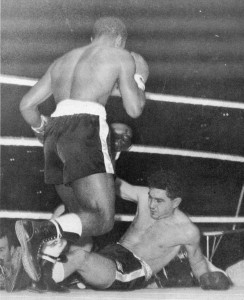

Ring Magazine boxing correspondent Bill Miller reported: “Davey Moore, the only boxer ranked by himself as the outstanding fighter of his class in The Ring’s International Ratings for 1960, proved his class again when he battered Danny Valdez into submission in 2:48 of the opening round of their world featherweight championship match in the Olympic Auditorium. Moore, defending his crown for the third time, made quick work of his opponent. He wasted no time tearing in for the ‘kill.’ The 21-year-old contender, who gained a place among the top ten in the international ratings due to his two triumphs over highly ranked Ricardo Gonzales of Argentina, proved a keen disappointment. Danny had been expected to press the issue, instead of which he was outclassed. In his bouts with Gonzales, then rated the top challenger for Moore’s crown, Valdez exhibition was all that could be desired, but against Davey he was a flop. With one notable exception, his kayo at the hands of Carlos Hernandez in Caracas, Moore has not been beaten in five years. He has faced the cream of the world’s talent. …. Most Valdez rooters were stunned when their favorite hit the canvas, landing on his side. An overhand right struck with such force; it sent Valdez spinning for the first knockdown he had suffered in his short career. He wobbled up at eight, but it was obvious he could not continue. Swiftly the title holder rushed forth for the kill. He pulled back his right and sent it with force again to the jaw, and his challenger went down for keeps.”

Ring Magazine boxing correspondent Bill Miller reported: “Davey Moore, the only boxer ranked by himself as the outstanding fighter of his class in The Ring’s International Ratings for 1960, proved his class again when he battered Danny Valdez into submission in 2:48 of the opening round of their world featherweight championship match in the Olympic Auditorium. Moore, defending his crown for the third time, made quick work of his opponent. He wasted no time tearing in for the ‘kill.’ The 21-year-old contender, who gained a place among the top ten in the international ratings due to his two triumphs over highly ranked Ricardo Gonzales of Argentina, proved a keen disappointment. Danny had been expected to press the issue, instead of which he was outclassed. In his bouts with Gonzales, then rated the top challenger for Moore’s crown, Valdez exhibition was all that could be desired, but against Davey he was a flop. With one notable exception, his kayo at the hands of Carlos Hernandez in Caracas, Moore has not been beaten in five years. He has faced the cream of the world’s talent. …. Most Valdez rooters were stunned when their favorite hit the canvas, landing on his side. An overhand right struck with such force; it sent Valdez spinning for the first knockdown he had suffered in his short career. He wobbled up at eight, but it was obvious he could not continue. Swiftly the title holder rushed forth for the kill. He pulled back his right and sent it with force again to the jaw, and his challenger went down for keeps.”

After the fight, Davey expressed interest in meeting Joe Brown for the lightweight title. Davey said, “I think it would be a good match here in Los Angeles. That will have to wait until after Brown’s fight with Dave Charnley, but I’m in no hurry.” Other possibilities mentioned were Terry Spinks of England, a rematch with Kazuo Takayama, and Carlos Hernandez of Venezuela. Carlos was Ring Magazine’s third-ranked lightweight and was still undefeated, 19-0-3 (13). Since the Moore fight, Carlos had defeated Gil Cadilli, Alfredo Urbina, Vicente Rivas, Angel Robinson Garcia, and Len Matthews and fought a draw with Kenny Lane.

Davey continued his busy schedule defeating Gil Cadilli, 30-19-7, in Las Vegas (W PTS 10), Felix Cervantes, 24-7-2, in Mexicali, Mexico (W PTS 10), Kid Iraputo, 20-10-3, in Juarez, Mexico (W TKO 6), and Felix Cervantes, 24-7-2, again, this time in Los Angeles (W KO 5), before ending his 1961 campaign in Tokyo, Japan with a title defense against number three ranked Kazuo Takayama.

Moore-Takayama II took place on November 13, 1961. During the first three rounds, Takayama, 45-12-9, charged in recklessly, firing punches from all angles. But Davey remained cool, cleverly picking off punches and looking for openings. In the fourth, a sizzling right to the chin sent Takayama wobbling backward on rubbery legs. From that point on Moore began the slow, painful process of eliminating Takayama as a threat by bouncing jabs, hooks, stinging rights, and dazzling combinations off Kazuo’s head and body. In the thirteenth round, Moore dropped Takayama with a steaming left-right combination to the jaw. The last two rounds brought out Davey’s human side as he eased up on the dazed Takayama. The decision was quite decisive and unanimous.

In the January 1962 issue of Boxing Illustrated, the editors stated, “The sawed-off ball of Fire, (little 5’ 2 1/2”) Davey Moore need not take a back seat to any fighter, at any weight, in the ring today. Since knocking out Hogan Kid Bassey in 1959 to win his title, boxer-slugger Moore has won 15 out of 16 fights against the world’s best featherweights. In 1961, with the title at stake, Davey eliminated Danny Valdez in less than a round. And without the title on the line, fiery Davey has been equally successful; bowling over Gracieux Lamperti, Ray Nobile, Fred Galiana, and Gil Cadilli. With his record now standing at 50 wins, 6 losses (only one since 1956), and one draw, Moore appears to be the most talented of all current champions.”

Davey was named Ring Magazine’s “Fighter of the Month” in their May 1962 issue for his impressive seventh-round TKO over lightweight Cisco Andrade, 46-11-1 (26), in Los Angeles on March 9, 1962. Davey handed Andrade only the second stoppage loss of his 59 fight career. The bout, witnessed by over 9,000 wildly cheering fans, ended after 2:05 seconds of the seventh round. Referee George Latka stopped the battle to save Andrade from further punishment. Ring correspondent Bill Miller’s coverage of the fight: “World featherweight champion Davey Moore easily outclassed veteran lightweight Cisco Andrade, 135, and accomplished something the lightweight king Joe Brown could not, when he stopped the Compton, California boxer. Moore looked sharp, fast and strong at 132 pounds. As for the fight itself it was fairly one sided. The first round was about even as they felt each other out, but then it was all Moore. He not only outpunched Andrade, but in the second and third rounds he outboxed him as he landed stinging jabs flush on Cisco’s face. In the third round Davey picked up the pace as he switched to a hooking attack, then in the fourth crossed Andrade up by scoring with right hand leads. Cisco tried to go for the big one in the fifth and sixth, but although he was able to land some solid punches, he never had Davey in trouble. With only seconds remaining in the sixth session, Davey landed a right hand smash flush on Cisco’s jaw. Andrade went down flat on his back. At five, he wobbled to his feet, pulling himself up with the aid of the ring ropes. The toll reached seven, and the bell rang, saving Cisco for another round. When the bell sent them on their way for the seventh round all Andrade had left was his fighting heart. Moore tore into him and let loose with lefts and rights to Andrade’s head and body. Cisco tried to fight back but could not make it and after 2:05 of the round had elapsed referee George Latka wisely stepped in and called a halt.”

Davey returned to Los Angeles in July for a tune up fight against Mexico’s Mario Diaz, (W KO 2) before heading to Helsinki, Finland to defend his title against Finland’s Olli Maeki on August 17, 1962. Davey enjoyed an easy payday against Olli Maeki, 8-1-1 (1). Finland’s first world championship bout was short but not sweet for the local fans. Maeki proved no match for Moore, and he was put away at 2:31 of the second round. Maeki had been dropped three times in the round before referee Barney Ross humanely intervened. The one sided fight didn’t help the pro-boxing contingent in Finland. There already was an anti-boxing feeling among Finnish legislators, and the beating absorbed by Maeki didn’t help matters.

Davey had been toying with the idea of going after the lightweight title. But, he felt before moving up in weight there was one fighter in his division he had not yet eliminated, Urtiminio “Sugar” Ramos. The 21-year-old Ramos was Davey’s mandatory challenger and dangerous. Since turning pro in 1957, just two months shy of his 16th birthday, Ramos had compiled an outstanding record of 38-1-3 (29). His only loss was by disqualification. Davey had two tune up fights with Fili Nava in San Antonio, Texas (W PTS 10) and Gil Cadilli in San Jose, CA (W TKO 5) before signing to meet Sugar Ramos on March 16, 1963. The fight was going to take place in Chavez Ravine, the stadium of the Los Angeles Dodgers, as part of the “Carnival of Champions,” three championship fights promoted by Cal Eaton and George Parnassus. The other two championships being contested were world welterweight champion Emile Griffith and challenger Luis Rodriquez, and Raymundo “Battling” Torres and Roberto Cruz for the vacant junior welterweight championship. The Carnival was to be televised nationally, but with less than 45 minutes until air time and about 15,000 people already seated, a driving, blinding rainstorm hit the stadium, leaving the promoters no alternative but to postpone the show. The Carnival was rescheduled for March 21st, and 26,142 fans showed up, bringing in more than a quarter of a million dollars.

The Carnival opened up with Luis Rodrquez winning a unanimous decision over Emile Griffith for the world welterweight title. Following the welterweight title fight, the featherweights took over. Moore was a 2 to 1 favorite to retain his title. Moore earned a reported $40,000 for his sixth title defense.

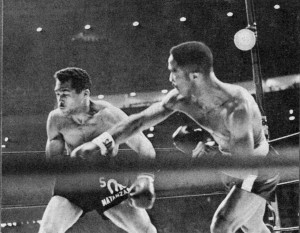

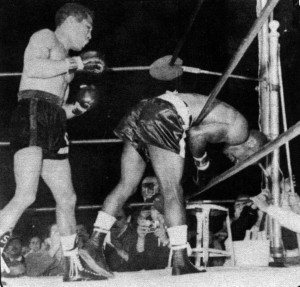

Here is how the fight was described in the June 1963 issue of Boxing Illustrated: “RAMOS-MOORE – To the thrilled spectators, it was a wild brawl between two real fighting men. It was the night’s best fight. Moore started like a Kentucky Derby winner breaking from the starting gate. In the second round Ramos was on the verge of being knocked out when Davey caught him with a left-right combination to the head. But the champ let him off the hook. In the fourth a right to the pit of the stomach nearly cut Ramos in half, but still he didn’t go down. Then, as the round swung into its final minute, the challenger started to come on. His jab was finding its mark on Moore’s face and the few hooks to the body landed solidly. In the fifth, the action hit a furious pace with Ramos starting to hurt Moore, slow him down, make him grab and hold. A right to the head staggered the champion and when he reached out to grab his foe, he was nailed with another right. Three more solid blows sent Davey stumbling across the ring with Ramos in hot pursuit. But the bell sounded just in the nick of time. That was the tragedy of the whole thing. Had the bell not rung, Moore probably would be alive today. Moore was badly battered in the sixth, but in the next round he surged back with surprising fire to bring Ramos to the verge of a knockout once again. But it was his final desperation attempt to save his crown. Davey’s face was splattered with blood in the eighth round as Ramos hurt him with a snapping one-two. The ninth was another brutal round for the brave champion. The

Here is how the fight was described in the June 1963 issue of Boxing Illustrated: “RAMOS-MOORE – To the thrilled spectators, it was a wild brawl between two real fighting men. It was the night’s best fight. Moore started like a Kentucky Derby winner breaking from the starting gate. In the second round Ramos was on the verge of being knocked out when Davey caught him with a left-right combination to the head. But the champ let him off the hook. In the fourth a right to the pit of the stomach nearly cut Ramos in half, but still he didn’t go down. Then, as the round swung into its final minute, the challenger started to come on. His jab was finding its mark on Moore’s face and the few hooks to the body landed solidly. In the fifth, the action hit a furious pace with Ramos starting to hurt Moore, slow him down, make him grab and hold. A right to the head staggered the champion and when he reached out to grab his foe, he was nailed with another right. Three more solid blows sent Davey stumbling across the ring with Ramos in hot pursuit. But the bell sounded just in the nick of time. That was the tragedy of the whole thing. Had the bell not rung, Moore probably would be alive today. Moore was badly battered in the sixth, but in the next round he surged back with surprising fire to bring Ramos to the verge of a knockout once again. But it was his final desperation attempt to save his crown. Davey’s face was splattered with blood in the eighth round as Ramos hurt him with a snapping one-two. The ninth was another brutal round for the brave champion. The  fatal tenth round was unpleasant to watch, even if you were rooting for Ramos. True, it is the way all real champions are supposed to go, but there is always something morbid about the expiration of great champions like Davey Moore. Ramos was after him like a tiger. He floored Moore for an eight count with a left hook. As Davey fell his head somehow cracked against the lower corner ropes. Although nobody realized it at the time, the fatal damage had been done. Amazingly enough, Moore got up and was still on his feet when the bell ended the round. Referee George Latka stopped the fight only when Willie Ketchum, Davey’s manager, asked him to do so during the rest period. Back in the dressing room, Davey expressed his desire to fight Ramos again. Then he passed out, never recovering consciousness.”

fatal tenth round was unpleasant to watch, even if you were rooting for Ramos. True, it is the way all real champions are supposed to go, but there is always something morbid about the expiration of great champions like Davey Moore. Ramos was after him like a tiger. He floored Moore for an eight count with a left hook. As Davey fell his head somehow cracked against the lower corner ropes. Although nobody realized it at the time, the fatal damage had been done. Amazingly enough, Moore got up and was still on his feet when the bell ended the round. Referee George Latka stopped the fight only when Willie Ketchum, Davey’s manager, asked him to do so during the rest period. Back in the dressing room, Davey expressed his desire to fight Ramos again. Then he passed out, never recovering consciousness.”

After the fight, Referee Latka said, “I knew something was wrong. Moore always seemed invincible to me. But tonight was different. His eyes looked okay, so were his reflexes. But it was his legs that bothered me. Around the fifth round, I began to worry … I’d never seen him stumble so much. He didn’t move like he usually does.”

News of Davey Moore’s tragic ending dominated world news and sports pages for weeks. There were cries from some political and religious circles to ban boxing, while those in the boxing community looked at ways to improve the safety of boxers (size of the gloves, extra padding for ring posts, etc.). There was also concern for the well-being of Davey’s young widow and five children. Willie Ketchum revealed the status of Davey’s finances while plans were completed for flying his body back to Springfield, Ohio, for funeral services. “Davey wasn’t a spender. He always put his money to work for his family. I’m not sure about the amount of cash in his bank account, but he’s got things to show for his fighting. He doesn’t owe anybody.” It was reported that the Moore family would start collecting a monthly income of $300, plus an undisclosed income from considerable real estate holdings. But, Geraldine said that the statements about the monthly income and the real estate holdings were false. The only real estate they owned was their home.

Regarding Davey’s purse from the Ramos fight, Geraldine only received half of Davey’s purse, minus expenses. She said her family got through the tragedy through the love and support of both sides of the Moore and Welch families. To supplement the family’s income, Geraldine took a position in Columbus, Ohio as a notary clerk connected to the governor’s office, where she worked for 32 years. She retired in 1996 and moved back to Springfield, Ohio, where she still resides.

Before Davey was buried, the Associated Press published the coroner’s autopsy report. “ – FINDINGS – A coroner’s autopsy shows that Davey Moore suffered three times the amount of brain damage originally indicated by an encephalogram after his fatal fight against Sugar Ramos. Moore’s backward plunge onto the lower strand of the ropes is believed by autopsy surgeons to have caused the massive damage that resulted in his death early Monday. The scores of jolting lefts that Ramos rained to the head and jaw of the featherweight champion were described as contributing factors. Coroner Theodore J. Curphey, reporting the findings of a two hour autopsy, said there were small hemorrhages and edema of the structures of the brain stem and also “large contusions in the midline of the cerebral hemisphere which were probably one of the major factors in bringing about this man’s demise.”

Services for Davey Moore were held at the Mount Zion Baptist Church in Springfield, Ohio. An estimated 5,000 persons paid their last respects. Flowers from across the country arrived at the funeral home. Among the flowers received was a spray of white lilies from Benny Paret’s widow Lucy. Geraldine Moore said she couldn’t estimate the number of telegrams of sympathy she had received. Messages of sympathy included telegrams from comedians Eddy Foy Jr. and Bob Hope. Governor James A. Rhodes led the stream of mourners, who spent most of his boyhood in Springfield and regarded Moore as a personal friend, and Mayor Clarence J. Waterman.

The public controversy over Davey’s death was even reflected in popular songs by artists such as Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Phil Ochs. On April 13, 1963, Bob Dyland gave a program of his compositions and introduced his newest song entitled “Who killed Davey Moore.”

During his ten year career, Davey defeated such men as Hogan “Kid” Bassey, Lauro Salas, Cisco Andrade, Kid Anahuac, Gil Cadilli, Sergio Caprari, Charley Riley, Fili Nava, Kazuo Takayama, Fred Galiana, Gracieux Lamperti, Frankie Valdez, Danny Valdez, Felix Cervantes, Mario Diaz, Ricardo Moreno, Hilario Morales, Bobby Neill, Vince Delgado, Roberto Garcia, Raimondo Nobile, Victor Manuel Quijano, Jose Luis Cotero, Pedro Tesis and Isidro Martinez.

On September 10, 1972, Springfield, Ohio, dedicated a park in Davey’s memory. The Davey Moore Park is located at 627 South Yellow Springs Street. The Park consists of 49 acres containing lighted softball diamonds, football and soccer fields, basketball courts, accessible playground equipment, shelter houses, and picnic areas. Unfortunately, most of Davey’s memorabilia was lost when the Cultural Center burned down several years ago.

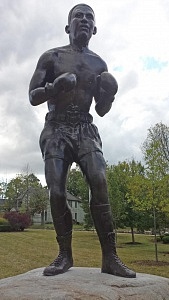

In September 2013, the city of Springfield unveiled an eight-foot statue of Davey sculpted by renowned Champaign County sculptor Mike Major in a park near South High School. The statue is the sixth of a prominent figure in Springfield and Clark County history, reminding people of the area’s unique heritage while also becoming something of a tourist attraction.

In September 2013, the city of Springfield unveiled an eight-foot statue of Davey sculpted by renowned Champaign County sculptor Mike Major in a park near South High School. The statue is the sixth of a prominent figure in Springfield and Clark County history, reminding people of the area’s unique heritage while also becoming something of a tourist attraction.

Sugar Ramos traveled from Mexico City to attend the ceremony and spoke through his friend and interpreter, Joe Flores. “It’s hard because it was always in my mind,” he said. “I’m always thinking about what happened and what I did, and it hurts, but that’s the law of life, so you have to do it.” The love the Moore family gave Ramos at the unveiling provided him with a way to heal emotional wounds that he’s held onto for the past 50 years.

I want to thank my good friend Stephen Gordon, Managing Editor of The Cyber Boxing Zone, who shares the same passion I do when it comes to Davey Moore. He spent time with Davey when he was eight and thirteen years old and shared his experiences with me in the accompanying piece.

References

- Boxing Illustrated, Articles and Fight Coverage

- Callis, Tracy, Private conversations, April-June 2009

- Gordon, Stephen, Private conversations, April-June 2009

- Los Angeles Times, Articles and Fight Coverage

- Major, Mike, Sculptor of the Davey Moore Sculpture Project

- New York Times, Articles and Fight Coverage

- NewspaperArchive.Com, Articles and Fight Coverage

- Photos courtesy of Antiquities of the Prize Ring and the IBRO

- Ring Magazine, Articles and, Fight Coverage

- United Press International, Articles and Fight Coverage

- WBUR.Org

Originally Published: IBRO Journal 102, June 2009