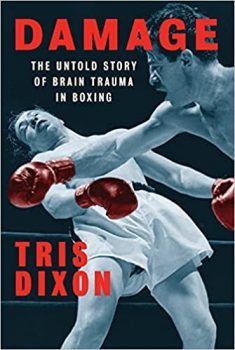

Book Review: “Damage: The Untold Story Of Brain Trauma In Boxing” By Tris Dixon

Boxing’s Human Demolition Derby (Courtesy of Bobby Franklin’s Boxing Over Broadway, July 4, 2021)

By Mike Silver

The wealth of information contained in this remarkable book is more important than 100 medical papers about brain damage in boxing because it is written in layman’s language and exposes the personal stories behind the cold statistics and scientific jargon. Its words should serve as a clarion call for action on behalf of the athletes for whom boxing is not so much a choice as a calling. In bringing attention to this serious topic Tris Dixon does not seek to abolish boxing—although there is a strong case to be made for that both medically and morally—but to try and make a dangerous sport less dangerous by shining a light on a subject that is too often ignored or neglected by the boxing establishment.

The first chapters reveal a litany of neurological studies that emphatically link boxing to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which is a medical term for brain damage caused by repetitive concussive and/or sub concussive blows to the head. At least 70 years before Dr. Bennet Omalu famously discovered and published his findings on chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American football players, neurologists in the 1920s and 1930s had already made that same connection as it relates to professional boxers. At that time CTE was known to the general public by a different name—“punch drunk”. The term was used to describe boxers “who were losing their faculties in the form of slurred speech, awkward movement, memory loss, and other degenerative behavioral changes.” Eventually scientists and neurologists stopped using the pejorative “punch drunk” and replaced it with the more elegant sounding “dementia pugilistica”, which is just another name for CTE.

That would mean from the beginning of the last century to the present thousands upon thousands of boxers have been afflicted with varying degrees of brain damage.

Subsequent studies indicated the condition was not confined to any specific population of prizefighter. “It was not just the old fighters who suffered from it”, writes Dixon. “Nor, as the early research showed, was it just novices, sparring partners, and fall guys. Some fighters were burnt out before others, some fought long, hard careers, some were ‘punchy’ after a dozen fights.” Most alarming of all was a consensus by the scientists that approximately 90% of all professional boxers were affected in some way. That would mean from the beginning of the last century to the present thousands upon thousands of boxers have been afflicted with varying degrees of brain damage.

CTE is a progressive condition that slowly but surely gets worse over time. Dixon describes the ongoing research that is attempting to understand why some boxers develop symptoms early and others seem able to function normally until their 50s or early 60s when they suddenly drop off the cliff, so to speak, and quickly descend into a haze of mental confusion and premature senility even though the boxer has retired from the ring and repeated head traumas are at an end.

In addition to explaining the science, Dixon does not shy away from questioning the moral ambiguities of the sport. He quotes Dr. Ernst Jokl, whose book The Medical Aspects of Boxing (1941) is considered a seminal work for its time: “Of all the major sports, boxing occupies a special position since its aim is that of producing injuries, more particularly to the brain…similar injuries occur in sports other than boxing, e.g., in football or wrestling. But here they are accidents rather than sequale of intentional acts. Only in boxing are traumatic injuries unavoidable even if the rules are adhered to.”

Second-impact syndrome, which can result in permanent brain damage, is a common occurrence in many prizefights and sparring sessions…

Dixon notes that in recent years researchers have determined that one of the most dangerous aspects of both boxing and football is second impact-syndrome “when someone suffers a second concussion while still suffering from the first.” Second-impact syndrome, which can result in permanent brain damage, is a common occurrence in many prizefights and sparring sessions yet “is not widely discussed in boxing when it should be a regular part of the conversation…[it] is one of the most serious threats to brain injury, both in the long and short term. In second-impact syndrome, the first hard hit has done more damage than anyone suspects and then the boxer takes a follow-up shot and life can be irreparably changed. A fighter can be hurt in sparring and still not be healed by fight night, when disaster can strike.” The danger is compounded in the presence of an incompetent referee or ringside physician. Dixon laments the fact that boxing does not have the equivalent of the “tap out” in mixed martial arts (MMA) contests. But the “I am willing to be carried out on my shield” mentality is embedded into the culture of this ancient sport and in the minds of its fighters. Even so, modern gloved boxing was never meant to be a human demolition derby or a fight to the death.

His (Ali’s) family did not want to believe or admit that boxing was the cause.

Of course no book on brain injuries in boxing would be complete without mentioning the most famous boxer of them all—Muhammad Ali. Dixon devotes several chapters to Ali, starting when Ali began to show symptoms of CTE while still fighting. By his early 40s (a few years after he retired) Ali’s hand tremors, slowing of his speech and movement noticeably worsened. His family did not want to believe or admit that boxing was the cause. They claimed that he had Parkinson’s disease and his condition had nothing to do with boxing. While it’s possible that in later years he may have developed Parkinson’s disease Dixon quotes several prominent doctors who state unequivocally that boxing was the primary cause of Ali’s infirmity.

Ali actually suffered from Parkinson’s syndrome, which is destruction by trauma to the same parts of the brain that are destroyed by someone who develops Parkinson’s disease. It is not the same as Parkinson’s disease and has a different cause.

Ali actually suffered from Parkinson’s syndrome, which is destruction by trauma to the same parts of the brain that are destroyed by someone who develops Parkinson’s disease. It is not the same as Parkinson’s disease and has a different cause. CTE, which can cause Parkinson’s syndrome, is identified at autopsy by the presence of tau protein in the brain. Tau gradually breaks down brain cells, causing the reduced state fighters find themselves in while they’re still alive. Dr. Robert Cantu, one of the world’s foremost neurosurgeons, and senior advisor to the NFL Head, Neck and Spine Committee states that “CTE is a highly serious issue itself, but it could also be an accelerant to other neurological illnesses”, something he is almost certain of. “Of the great fighters who died and were diagnosed with dementia, Parkinson’s, ALS, or Alzheimer’s over the years, there is not only a chance that it was just CTE misdiagnosed, but it could have triggered different medical problems. You’ve got dementia, Alzhiemer’s, Parkinson’s but you got it twenty or thirty years earlier. But there are pure cases of CTE, and in those cases they’re probably not an accelerant, just the result.” Dr. Ann McKee, another renowned neuropathologist interviewed by Dixon, “has checked more than twenty-five boxers’ brains and has yet to see one that has not had CTE from fighting.”

“Statistics from CompuBox, which compiled the punch stats from 47 of Ali’s 61 professional fights, revealed he was hit 8,877 times.”

Dixon tells us that in 1981 a CAT scan of Ali’s brain was taken just before his last fight. It showed the type of atrophy that show up in 50 percent of boxers with more than 20 bouts—a percentage far higher than in the general population. This type of abnormality is found four times as frequently in boxers as in non-boxers. In the latter half of his 20 year career Ali absorbed a huge number of punches: “Statistics from CompuBox, which compiled the punch stats from 47 of Ali’s 61 professional fights, revealed he was hit 8,877 times.” That number does not include all the hits he took in countless rounds of sparring. Ali had stayed too long and paid a terrible price. At the time of his death at the age of 74 in 2016 Ali “had been unwell for 3 decades.” His brain damage was severe, and it was all due to boxing—not Parkinson’s disease as has so often erroneously been credited for his condition. Had Ali donated his brain for research the diagnosis of CTE would have been confirmed, as it has with the dozens of deceased boxers (and many more football players) who willed their brains to science. Instead, the most recognizable face on the planet was propped up as an advocate to find a cure for Parkinson’s disease. All well and good, but what he should have been was the poster person for brain damage in boxing.

Frankie (Pryor) told Dixon she wished that Ali’s family had publicly acknowledged the reason behind the icon’s demise as that could have helped countless more fighters understand what happened to them.

Frankie Pryor knows about CTE first hand. She is one of several wives of former champions who were interviewed by Dixon. Frankie’s late husband, Aaron “Hawk” Pryor, was one of the greatest fighters of the past 50 years. But, like so many others, he became a boxing casualty. Frankie told Dixon she wished that Ali’s family had publicly acknowledged the reason behind the icon’s demise as that could have helped countless more fighters understand what happened to them. “It was kind of always my one regret because the one fighter who had the notoriety and could have brought a lot of attention to this was Ali”, she said. “And then they went off on this Parkinson’s thing…I don’t think it was done maliciously. Maybe Lonnie [Ali’s wife] didn’t fully understand the impact, but just to say, ‘it wasn’t boxing, it was Parkinson’s.’ No it wasn’t.”

How sad for this tragic sport that there is no Muhammad Ali Center for patients and family members who are dealing with boxing induced brain damage.

There is a research center named for Ali in Phoenix, Arizona—the Muhammad Ali Parkinson’s Center. It is described as “a comprehensive resource center for patients and family members dealing with Parkinson’s disease.” That is the legacy the champ’s family prefers. But what does that legacy mean to the legions of damaged boxers who, like Ali, are suffering the debilitating effects of chronic traumatic encephalopathy? How sad for this tragic sport that there is no Muhammad Ali Center for patients and family members who are dealing with boxing induced brain damage.

Nevertheless, research into the causes and treatment of CTE continues thanks to the efforts of Dr. Robert Cantu, Dr. Ann McKee, and Dr. Charles Bernick. They are at the forefront of the science seeking to detect and track the earliest and most subtle signs of brain injury in those exposed to head trauma. A remedy to treat, or perhaps even reverse, the damage done by the tau protein is a long way off. Many of the studies will not bear fruit for another 10 or even twenty years. In the meantime what can be done to limit the damage? The answer: Plenty, but only if there is the will to change. Among the changes that Dixon says should be considered are glove size, reducing exposure by limiting the number of rounds and their duration, better education for referees and ringside physicians, and the use of head guards.

Dixon points out “the lack of detailed education with trainers, through commissions or sanctioning bodies. No memos have gone out since CTE was confirmed.

There are many people and organizations in the professional boxing world that are not anxious to accept the findings of the scientists or do anything of significance that might make the sport less dangerous. Dixon points out “the lack of detailed education with trainers, through commissions or sanctioning bodies. No memos have gone out since CTE was confirmed. Nothing changed, yet this—punch–drunk syndrome—was boxing’s problem before it was anyone else’s.” In the words of Chris Nowinski, a former Harvard football player, WWE wrestler, and founder of an organization called the Concussion Legacy, “Fighters are on their own…If you compare boxing to what’s happening in football or other sports there’s virtually no one looking out for the athletes…Without a centralized organization, there’s nowhere for boxers to get educated, no go to source, no self-help manuals, and no union.” Absent a centralized organization or boxers’ union (don’t hold your breath waiting for that to happen) the major promoter/entrepreneurs are in control. Referees and ringside officials are licensed by state boxing commissions but they are paid by the promoter. This is a clear conflict of interest as the promoter has a vested interest in seeing that a promising fighter under contract to him does not lose. Referees and ringside physicians should be completely independent of having anything to do with a promoter or sanctioning organization. Dr. Margaret Goodman, a respected former ringside physician for the Nevada Boxing Commission, explained how a promoter’s influence can determine who officiates: “If you [the ringside physician] stop a fight or recommend a fight should be stopped from a promoter that has big connections with the commission, you’re never going to work another fight again. Same thing for the referees. Same thing for the judges…there are too many outside influences, and the overall health of the sport has not improved as much as it could from those factors as well, which most people don’t take into account.” No one wants to see a boxer seriously injured but with no effective oversight in place the pervasive greed and corruption of promoters and sanctioning organizations takes precedence over any concern for the boxer’s health.

One cannot help but be moved and disturbed by the author’s accounts of his interviews with these damaged gladiators.

The best parts of the book involve Dixon’s description of his personal interaction with the boxers and their families. One cannot help but be moved and disturbed by the author’s accounts of his interviews with these damaged gladiators. Although the boxers were concerned about the long term effects of their punishing careers most said—and it speaks to the pull of this sport and how central it is to their lives—that they would do it again even if it meant winding up with brain damage.

“Fighters must be made to understand the cumulative toll sparring and boxing takes on them and they need to be prepared to walk away when the time comes.”

Dixon concludes with the following words: “The sport might not be able to save every fighter but it must give them the best chance of saving them from themselves. Fighters must be made to understand the cumulative toll sparring and boxing takes on them and they need to be prepared to walk away when the time comes. That is the hardest part for many fighters, and it’s why the sport should do more to help as they start a new chapter….It’s time boxing confronts its own worst problem, stops ignoring it, and steps up to address it at all levels. This is a sport of courage and it will take bravery but it’s happened in football, soccer, and rugby although it should not be up to other sports to take on boxing’s biggest fight.” It is a fight that is long overdue.

Damage: The Untold Story Of Brain Trauma In Boxing

By Tris Dixon

Hamilcar Publications, 227 Pages, $29.99

****************

Mike Silver’s books include “The Arc of Boxing: The Rise and Decline of the Sweet Science” and “Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing-A Photographic History”; His most recent book is “The Night the Referee Hit Back: Memorable Moments From the World of Boxing”.