Where have you gone Andy Callahan?

By Christine Lewis

In 2003 the Lawrence Historical Center received a bronze plaque from Gerard Ryan of Pembroke, MA. commemorating Andy Callahan. The Lawrence volunteers knew Andy Callahan was a boxer but where the plaque came from remained a mystery – something to do with the Big Dig. Further investigation revealed the plaque had hung on the wall of the old Boston Garden. The fact that this was a mystery to anyone in Lawrence shows how far out of the mainstream consciousness boxing and Andy Callahan have fallen.

Lawrence, Massachusetts is a tough former mill city located 27 miles north of Boston. Incorporated in 1853, the merchant founders built huge factories that were powered by the waters of the Merrimack River. Boxing has had a long presence in Lawrence: the earliest record was an 1860’s prizefight that ended in a draw between Lawrencian Frank AcAleer and Bostonian Professor Levett. In 1887, in an effort to avoid unfriendly police interference, Lawrence was chosen as the location for the World Lightweight title fight between Jack McAuliffe and Canadian challenger Harry Gilmore. The fight was staged in a blacksmith shop on the corner of Broadway and Merrimack Street, where White Street Paint currently operates. The ring consisted of three ropes and a solid brick wall that was put to clever use by both boxers throughout the 28-round fight. McAuliffe won and Lawrence further established its reputation as a fight-friendly town.

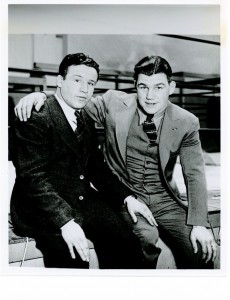

Born in 1910, Andy Callahan came of age in a time and a town where boys were more likely to don boxing gloves than baseball mitts. Callahan became the best fighter to come out of New England in his day (1928-1938). He held three titles simultaneously: New England Lightweight, Middleweight and Welterweight. He was afraid of nothing and often met opponents who outweighed him by as much as twenty pounds. He was the first New England boxer to die in WWII. His status as hometown hero became mythic and for many years Lawrencians would mark the anniversary of his death with solemn dedications and fond newspaper remembrances.

Andy Callahan grew up in the Irish Prospect Hill neighborhood. His father Peter worked as a stoker in the Lawrence Gas Works and possessed the same incredible endurance his son displayed in the ring. Andy was a rather unremarkable student at the parish school of St.Laurence O’Toole and spent a good deal of his time getting his knuckles rapped by Sister Ellen Patricia.

At the age of 14 Andy began visiting the gym at the old St. Anne’s on Haverhill Street, home of the current Lawrence Boxing Club. He traveled the local circuit garnering his share of wins and losses. Callahan’s training improved when, at age 16, he received tutelage from a local promoter, William (Tee Hee) McDonough, manager of Lawrence great Tommy “Kloby” Corcoran and Arthur Flynn. In the spring of 1927 Andy Callahan won the amateur New England featherweight championship at the old Boston Arena, and soon after began his professional career KO’ing Joe Morandi in one round at nearby Salisbury Beach.

Callahan’s wallet had a picture of his idol, Mickey Walker, an Irish-American welterweight from Elizabeth, NJ who fought and beat several heavyweight contenders. Like Walker, Andy picked up the moniker “The Toy Bulldog” for his small stature, aggressive attack and fearless demeanor. (Callahan was only 5ft 6 inches tall, but unlike most lightweights, he had massive shoulders.) Also like Walker, Callahan fought men who outweighed him by 20 pounds and won.

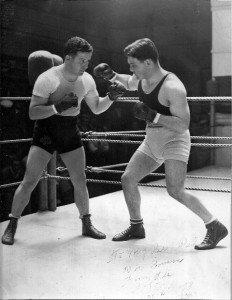

The 19 year old pro became part of renowned Boston manager John Buckley’s stable and plowed through opponents, building quite a reputation with fans and the press. Throughout much of his career, Callahan had to do without sparring partners due to his inability to hold back in training. While preparing for a March 1929 fight with Baby Stribling, (younger brother of W.L. Stribling), as part of the Sharkey/W.L.Stribling card in Miami, Sharkey’s sparring partner, a plus-200 pound man named Hoffman offered to spar with Callahan, strictly for laughs. Callahan flattened Hoffman with a left and the big man went down, apparently for quite awhile. (Callahan was to have trouble with his left hand after this event.) Baby Stribling’s camp heard about the incident and it was reported that Baby came down with a quick case of the measles and was replaced by a Joe McKenzie. It appeared to those in the audience that Callahan had his hands full with McKenzie. Buckley, sitting behind a reporter, yelled some instruction to Callahan during the second round. Callahan turned his back to his opponent and shouted to Buckley “Watch this one” and without stopping to look around knocked McKenzie down with a stiff right. At 19, Callahan’s raucous demeanor and winning record helped him build a large fan base.

Callahan’s first major loss was in December, 1929 to Louis Kaplan, featherweight champion from Meriden, CT. Callahan broke his left hand on Kaplan’s jaw in the first round, (the same left he damaged sparring with Hoffman) knocking Kaplan down for a the first time in his career. Callahan proceeded to battle for nine more rounds with a broken hand and lost by decision.

After taking some time off to heal, Callahan came back and in May of 1930 and began what would be the first of seven matches against Italian featherweight Sammy Fuller. The rivalry between the fighters and their fan base was intense. Promoters knew that matching an Irish-American fighter with either an Italian-American or Jewish-American fighter would guarantee big box office money. Callahan won and the two met again later in November of 1931, resulting in Callahan winning Fuller’s New England Lightweight title. This set him up for a New England title fight that many felt was insane, a match with New England middleweight and welterweight champ, Lou Brouillard. The larger and stronger of the two, Brouillard was thought to have the ability to seriously hurt Callahan. Even Manager Buckley began to have his doubts leading up to the match. The only person unconcerned was Callahan, who turned to his nervous manager before climbing between the ropes: “So, you’re leading a lamb to slaughter, eh?” Brouillard’s team shouted to Lou to “Watch out for his left” but Callahan’s trainers had anticipated their opponent’s strategy and adjusted brilliantly. Andy Callahan was a southpaw but his right was just as powerful as his left and he used this to his advantage. Brouillard was unable to figure out how to avoid Callahan’s stinging right. Camp Brouillard also warned their fighter to watch out for a wild, swinging battler, instead, Callahan carefully and thoughtfully out-boxed the bigger man. Andy Callahan won eight of the twelve rounds and walked out of the ring a triple-crown winner.

Buckley worked his managerial magic and finagled a title fight for Callahan with World Middleweight Champ, Vince Dundee. Many in the matchmaking process felt Callahan was too small to fight 158-pound Dundee, but were surprised when Andy weighed in at 150 pounds. Over $20,000 worth of seats had been sold when Buckley fessed up to the promoter that Callahan really weighed 136 and that he’d altered the weight used on the scale. By drilling out the weight and padding it with Mercury or some other substance, Buckley had managed to add 15 pounds to Callahan’s 136, bringing him within 8 pounds of his opponent, thus satisfying weight restrictions mandated by the boxing commission rules. It was too late to call the match off; the two men went ahead knowing they had to perform some serious trickery to change out the weight for the scale while distracting the ever-present press. The first round was all Callahan with Andy knocking Dundee to the mat and winning 10 out of the 15 rounds. The judges, who were handpicked by Dundee, gave the fight to Dundee by one point and all hell broke loose. A furious Buckley jumped up on a table as the crowd was filing out of the Garden and shouted, “They give it to me tonight…Callahan weighed only 135!” The aftermath resulted in Buckley being fined and suspended for six months. It has been said by those who knew him best that Andy Callahan was heartbroken and this started him on the road to ruin.

Perhaps too soon after his loss to Dundee, Callahan met up with Werther Arcelli, and Italian from Roxbury, MA and lost his New England Welterweight title. Andy appeared “sluggish” and not in the best shape. Callahan suffered an open cut on the bridge of his nose in the 2nd round that, without Buckley in his corner, no one could control. Only in the 7th round did Callahan come alive, landing a couple of solid belts in Arcelli’s “spaghetti locker and a hefty lick or two in the chops.” During the years 1935-1936 Callahan only had six fights with mixed results. People didn’t know which Andy Callahan would show up to the ring: the southpaw sensation or a distracted, ill-prepared boxer. Callahan was still better than most, it was more that he no longer performed with the same consistent bravado he demonstrated during the first half of his career. The highpoint of 1937 were the three grudge matches with Boston’s Sammy Fuller. He eventually parted ways with John Buckley, claiming to the press that Buckley “kept him idle for months at a time and then expected him to get in shape on 10 days notice.”

Buckley was a businessman and as much as he loved Andy, boxing was business. Callahan, while not a criminal, spent much of his downtime drinking with his Lawrence buddies, brawling in back alleys, pulling fire alarms and other such juvenile pranks. Such behavior hardly left Andy in fighting form. Callahan’s disdain of training was legendary: good friend and fellow Lawrence pugilist Arthur Flynn said, “that at various times in his career he entered the ring with a haircut and shave as his only training.” Andy’s final fight was with Young Byron in Boston in January of 1940. Arthur Flynn was Andy’s manager for this fight and Andy won, ending a career that saw him beat former world champions, fight bigger men without fear and come within a point of winning the world middleweight championship of the world.

Callahan enlisted in the army on April 13th, 1942 and became a fight instructor at Camp Wheeler in Alabama. During the year he was at Wheeler, Andy Callahan was promoted to the rank of corporal and soon after his promotion he left the base for a night on the town. He stayed beyond his allowed time and after returning to the base he was called before the company commander who said: “Sit down, Corporal Callahan.” Andy sat down. “Stand up, Private Callahan.” He was later stationed at Camp Edwards in North Carolina and when his outfit was preparing to go overseas, Andy asked to go with them. Callahan was 32 years old and his commander wanted him to stay stateside and continue serving as a boxing instructor, but Andy was never one to back down from a fight. In March of 1943, he left for Northern Africa and from there went on to Sicily and the invasion of Italy. He was with the 36th Division, Company D, 101st Infantry, invading Monte Cassino during intense fighting when he was hit by a large shell – living only a few moments.

The Boston fight world mourned the loss of their local here. On December 10, 1943 the Boston Boxing Association officially changed its name to the Callahan AC in order to honor Andy Callahan. All the New England greats who had fought Callahan showed up that night at Mechanics Building to honor Andy Callahan. Sammy Fuller, Callahan’s archrival, spoke tearfully for all the boxers present when he said: “I want to salute the greatest little boxer that ever lived. He dies so that the American flag might wave. God Bless his soul”. (Callahan and Fuller had become friendly after retiring from the ring; they developed a grudging respect for one another.) On that day, Dave Egan of the Boston Record said “They have found a name that links the past of boxing to the future, that stands for aggressiveness and courage and invincible honesty in the ring and tell the generations that are coming that once upon a time, to its eternal credit, this rough and lusty sport produced a fighter of the great tradition who fought to the very death for them and all future generations.”

His body didn’t make it back to Lawrence untill 1948, not unusual for soldiers killed abroad during the war. On September 19th, 1948, Andy Callahan came home to the city that loved him fiercely.

In 1979, a the Lawrence Veterans Council got together and dedicated the North Canal in Lawrence to Andy Callahan, renaming it the Andy Callahan Waterway, with a metal plaque and two commemorative signs. Sadly, both the signs and the plaque were quickly stolen by vandals and never replaced. The city of Lawrence had changed, many of the men who knew Andy had either passed or moved away. Today, the remaining memories of Andy Callahan are traded like prized urban legends.

Author’s note: I became involved in boxing research after seeing a picture of Andy Callahan and finding very little written on this very engaging character. I don’t feel I can rest until there is permanent, un-erasable documentation of this great Lawrencian…or at the very least, a garage band named the Andy Callahan’s.

Published in IBRO Journal 101, March 2009