HIS NAME IS GEORGE DIXON

by Roger Zotti

I am a white, middle-class author already more than a decade older than [George] Dixon when he died. My experiences are in no way those of Dixon. I approached this book with eyes open to those limitations. I hope this book inspires others to take up Dixon and view his life through new perspectives. Agree with me. Disagree. Build on what I have found. Splinter off in new directions. Dixon is worth dozens of books exploring his life.

Other authors and scholars of different backgrounds or expertise will bring a whole new take to his life. Gender. Race. Politics. City building. Sports spectacle. Mass media. International travel. Legal. The lenses through which you could view Dixon’s life are plentiful and each would be as valid and exciting.

No one book, no one author, can hope to tell the entire story of a life.

Jason Winders

1

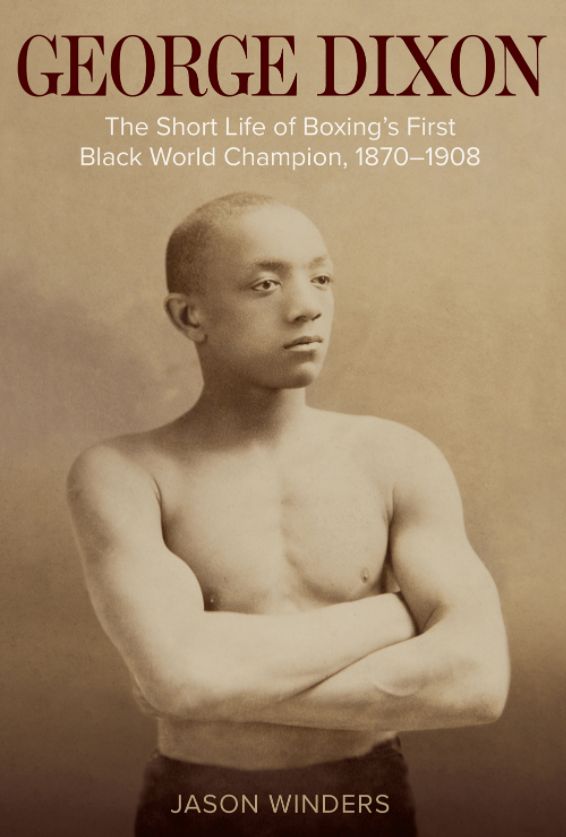

A bantamweight champion and later ruler of the featherweight division, the great George Dixon, who fought from 1886 to 1906, has finally received the recognition he deserves, thanks to Jason Winders’ exhaustively researched and well-crafted biography titled George Dixon: The Short life of Boxing’s First Black World Champion, 1870-1908 (University of Arkansas).

Raised in Boston, but born in Canada, Dixon was “the first Black world champion of any sport and the first Black world boxing champion in any division,” Winders’ press release points out,” and that“ despite his triumphs, Dixon has been lost to history, overshadowed by Black athletes whose activism against white supremacy far exceeded his own.”

2

In his Introduction, one of the best I’ve ever read, Winders, a sports historian and journalist who resides in London, Ontario, writes that “George Dixon was a self-taught genius whose peerless exploits in the ring inspired a previously unseen pride among Black America that often spilled into the city streets across the country. He fought constantly as a professional—maybe against a thousand opponents in his lifetime.” (According to Boxrec.com Dixon’s record was 67-30-57).

Most of those fights, Winders writes, were exhibitions but “a hundred or so of [them] were chronicled by both Black and white presses. . . . His championship reign ushered in an embrace of Black athletes at the highest echelons of sport,” Winders continues. “To a Black culture cementing its first national heroes, George Dixon was the single-most significant athlete of nineteenth-century America.”

3

Roger Zotti: What prompted you to write your book?

Jason Winders: Here was . . . a man who climbed to the heights of his profession, was celebrated in both the white and black presses of his day, accumulated fame around the world and fortune on levels rarely seen for a Black man of his era, and he was all but forgotten outside those who love the history of boxing.

What happened? This man should be mentioned alongside others who changed the conversation in sport and society, people like Jackie Robinson or Willie O’Ree. . . . What forces nearly erased Dixon from history? I wanted to know.

RZ: . . . most challenging about writing it?

JW: George Dixon is a ghost. Lots of factors play into that. His prime fell within one of boxing’s many “Dark Ages,” as Liebling once described the time between John L. Sullivan’s reign as heavyweight champion and the rise of Jack Johnson.

Aside from Dixon, the era was one of champions with little staying power and challengers of little distinction in all weight classes. Combine those circumstances with the sport’s questionable legal and moral standing around the globe, as well as white-dominated media who painted Black boxers in a biased light, and you see how the memories of many from that time have faded.

I was lucky that Dixon’s paper trail is long, and well-worn in places by would-be popular chroniclers. Yet it remains remarkably limited. During his lifetime, Dixon’s story inside the ring was richly told, as his major post-1890 bouts were covered in great detail.

However, little exists outside the ring, and all but nothing in Dixon’s own voice — no journals, no letters, no grand autobiographies. That left his story to the fates of time – and in the hands of those who had little interest in preserving an accurate portrait of the man.

RZ: What do you hope readers take from your book?

JW: I owe everything to the books and authors I have read. Richly detailed reads, both fiction and non-fiction, spark ideas in me, inspire me to tell stories in different ways, send me running to other books to find out more.

George Dixon features a cast of hundreds of people in stories playing out around the world. I hope people walk away from my book inspired to tell stories about the people and events they read about on these pages. I would love to hear someone interviewed in the future saying, “I was reading George Dixon by Jason Winders and it really inspired me to …”

RZ: Is there anything else you’d like readers to know about you and/or your book?

I have written a history of George Dixon. Not the history. It is important for people to understand that distinction. Gone are the days where we look to a single book as the absolute final word on a subject, especially when that subject is another human being.

4

My favorite chapter in Winders’ book—and it’s difficult to pick one because every chapter is significant—is the fourth, “No Hamlet without Hamlet.”

First, though, a word about Dixon’s manager-trainer Tom O’Rourke for, Winders writes, “To understand George Dixon, you must understand Tom O’Rourke. No single person is tied more directly to shaping the eventual champion than the Boston-born manager, a caricature of a nineteenth century sport, a wheeler, a dealer, and a showman on par with the greats.”

Unfortunately but maybe predictably, Dixon’s relationship with O’ Rourke eventually developed into a “power struggle” that “would continue for the rest of their partnership.”

Then, too, as Dixon grew older, his skills and health in decline, O’Rourke “no longer saw Dixon as an investment to be protected,“ Winders writes. He “had become a burden no longer of worthy consideration.”

I don’t think there’s a way to sum up the complex O’Rourke, except to quote what Winders writes about him: “Without [Rourke] in his corner Dixon would never have become a world champion. . . . But there was the dark, controlling O’Rourke who . . . . had no use for anyone he saw as having no use to him.”

Turning to the “No Hamlet without Hamlet” chapter, Winders’ most salient point concerns the featherweight title fight between Dixon and Brooklyn’s Jack Skelly on September 6, 1892, and its aftermath.

According to the Boston Globe, which Winders quotes, the “fight will test the color line in New Orleans, as it will be the first time a colored pugilist ever sparred in that city.”

Fight time! When Skelly entered the ring “the room erupted,” while Dixon’s “entrance was mixed.” As the fight progressed it was clear that Skelly, though game, was no match for Dixon, who ended matters in round eight.

Winders writes: “After a heavy exchange ”Skelly, who was bloodied and floored several times before the eighth round, “was beaten to the ground with terrible right- and left-handed swings. Try as he might, the challenger could not get up before the ten seconds elapsed.”

As for the repercussions following Dixon’s victory, Winders quotes the Detroit Plaindealer as announcing that “The feeling is actually very bitter, and it would have been better for the peace of the community if there had been no prizefight this evening.”And because the South believed that “masculinity was power, and, as such, translated itself into economic, political, or physical power,” Dixon’s knockout of Shelly “drew ire because it challenged deep-set notions of superiority upon which Southern society was based.”

Packed with drama, the true life kind, the “Hamlet” chapter is the book’s strongest and longest. In addition to a detailed account of the Dixon-Skelly fight, among the other issues Winders astutely covers are the Plessy vs Ferguson ruling, Jim Crow, the Carnival of Champions, Skelly’s life after boxing, the downfall of John L. Sullivan, and lynch law.

As you continue reading the later chapters of George Dixon, you’ll learn that after Dixon’s impressive victory over Skelly,“ we start to see societal forces shift somewhat against him” . . . You’ll learn that the North had its racial prejudices, too, for “To say race never colored fights in the North would be unfair,” and Dixon’s “fears were no longer limited to the South” . . . You’ll learn of “the pure bile that existed between the white power structure of the nation [and] the entire Black race” . . . You’ll learn the extent to which Dixon’s boxing skills had eroded.

More: In the final chapters you’ll become aware of Dixon’s demons—“drinking, gambling, violence”—and that ”his exploits outside the ring were gaining far more notoriety than those inside it” . . . You’ll become aware that after Terry McGovern soundly trounced him in 1900, the January 13 edition of Colored Magazine, a Dixon supporter, correctly wrote that Dixon “had ‘enlisted in that vast army of fighters who went into the ring once too often’” . . .

You’ll be made aware Dixon died “broken in health, penniless, and stripped of all honors won in the ring,” and sadly many of “the young fighters who filed past his [casket] did not know of Dixon as a champion, [but] their elders were deeply disturbed by the Dixon in front of them versus the one they remembered from just fifteen years earlier.”

5

Kudos to Jason Winders. In George Dixon he shares his enormous knowledge about Dixon’s life inside and outside the squared circle. At the same time, his book is both a vivid depiction of the America in which Dixon lived and a big step toward recognizing his importance in history.

Jason Winders is a journalist and sport historian who lives in London, Ontario.

For more information, visit the University of Arkansas Press or purchase wherever books are sold.

A regular contributor to the IBRO Journal, Roger Zotti has written two books about boxing, Friday Night World and The Proper Pugilist. His latest book of essays, now available, is titled Jack Kerouac and the Whiz Kids. He can be reached at rogerzotti@aol.com.