Jose Becerra: The Guadalajara Cobra

by Dan Cuoco

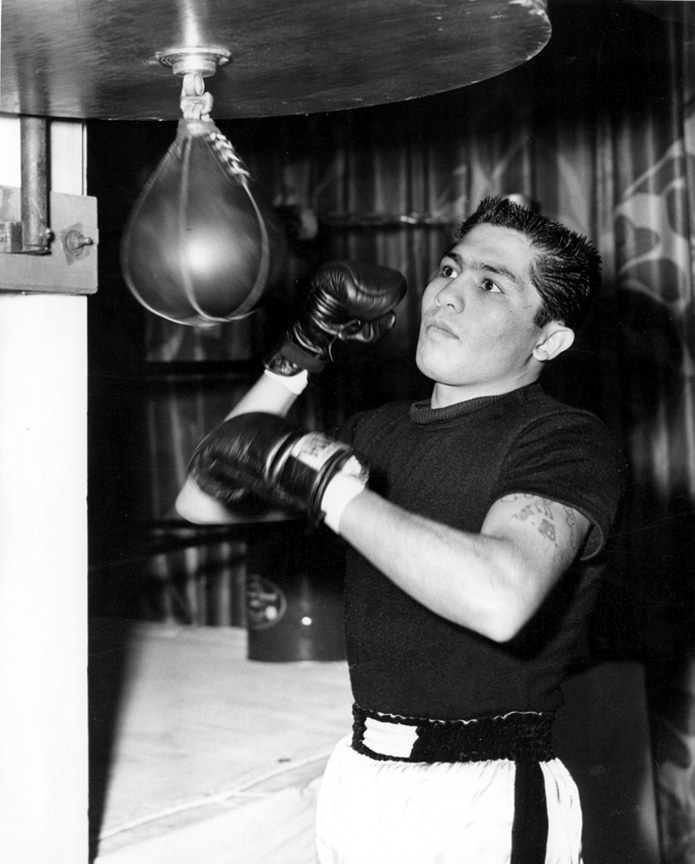

Jose Becerra was born on April 15, 1936 in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. He was the second oldest of five children (two brothers and two sisters). Jose became interested in boxing through a friend. He started in the Mexican Golden Gloves and had thirty amateur fights, winning all but two. Coming from a poor background, he decided to turn professional to earn a few pesos to help feed the family. At the time he turned professional, he had no thoughts of big purses or titles. Boxing was just a means to earn a meager living.

Jose Becerra was born on April 15, 1936 in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. He was the second oldest of five children (two brothers and two sisters). Jose became interested in boxing through a friend. He started in the Mexican Golden Gloves and had thirty amateur fights, winning all but two. Coming from a poor background, he decided to turn professional to earn a few pesos to help feed the family. At the time he turned professional, he had no thoughts of big purses or titles. Boxing was just a means to earn a meager living.

Young Jose came under the tutelage of Pancho Rosales, who for over thirty years had been Mexico’s leading developer of ring talent. On August 30, 1953, 17-year-old Jose Becerra made his professional debut with a fourth round knockout victory over Ray Gomez in Guadalajara, Mexico.

Jose quickly established himself as a comer by winning his first eighteen fights (all six rounders) over credible opposition. Most of his fights took place in Guadalajara, and he was quickly becoming a favorite because of his damaging punch. Nine of his eighteen opponents were knockout victims.

Jose tasted defeat for the first time when the more experienced Luis Ibarra outpointed him in six rounds on October 3, 1954. Fifteen days later Jose started another winning streak that saw him go undefeated in thirteen fights, with only a ten round draw with featherweight Danny Bedolla marring the streak. Eight of his victories were by knockout. Claudio Martinez put a temporary halt to Jose’s rise when he outpointed the 19 year-older on February 18, 1956 in Guadalajara.

Less than a month later Jose locked horns with another 19-year-old up and coming bantamweight named German Ohm. Trailing on points, Jose was able to cut Ohm’s eyebrows and escape with a sixth round technical knockout. The fight was the toughest of Jose’s career. Jose won five more fights before being matched with Ohm again. This time he wasn’t so lucky. Since their last fight, Ohm had knocked out Baby Ruiz in one round and was rated ninth in the world ratings. The rematch took place on October 18, 1956 before a packed arena. Ohm was better than Jose that night and gave him a boxing lesson en route to a unanimous ten round decision.

In 1957 Jose hit his stride as a big timer. Early that year he ended the winning streak of the veteran Cuban bantamweight Manuel Armenteros, who for many years had been among the top men in the division. At the time Jose defeated him, Armenteros was a big favorite in Mexico, successfully touring from city to city. He followed this victory with two easy ten round decision victories over another up and coming Mexican bantam named Jose Medel, who was one month shy of his 19th birthday, had turned pro at 17, and had already met and held his own with most of Mexico’s toughest flyweights and bantamweights. He entered the ring with Becerra sporting a record of 20-4-3, with 14 kayos.

His victories over Armenteros and Medel moved him into the world ratings on April 17, 1957. He entered as the number ten bantam in the world. Ahead of him in the ratings from Mexico were his idol Raul Macias at number one and German Ohm at number five.

After going undefeated in twelve fights since his loss to Ohm, Jose came to Los Angeles to fight Dwight Hawkins. The date was November 16, 1957. It was going to be a big night because Mexican ring idol Raul (Raton) Macias holder of the NBA bantamweight title was meeting Alphonse Halimi for the undisputed world title. All of Mexico was worked up over the fight. Thousands of Mexican fight fans made the trek from Mexico and joined those already living in LA in making a Mexican holiday of the event.

Even Jose got caught up by the occasion. He found it hard to keep his mind on his own fight that night, even though he knew Hawkins was a dangerous, murderous puncher. Macias lost a decisive fifteen round decision to Halimi – and all Mexico mourned. Because of television scheduling, Jose’s fight came on after the championship fight and Becerra too was in mourning. He later said, “I was so upset by Macias’ loss I didn’t care.” An unmotivated Becerra was stopped in the fourth round.

Jose stayed out of the ring for three months and came back a much more dedicated fighter. During the next year and a half he ran off fifteen consecutive victories, thirteen by knockout, to find himself the mandatory challenger for Alphonse Halimi’s bantamweight crown. Among his kayo victims were Dwight Hawkins (ko 9), Willie Parker (ko 2), Little Cezar (ko 4), Jose Luis Mora (ko 3), Ross Padilla (ko 1), Mario D’Agata (tko 10), and Billy Peacock (ko 1). His most impressive victory was when he fought Mario D’Agata, former world bantamweight champion in Los Angeles on February 5, 1959. D’Agata proudly boasted that he had never been floored in his life. D’Agata, like Jake LaMotta before him when he fought Ray Robinson, could continue that boast after the fight. But Becerra pounded him so relentlessly D’Agata was forced to call it quits in ten rounds. The stoppage was the only time the ex-champion failed to finish a fight in a career that spanned twelve years and 67 fights.

During this eighteen-month stretch, Jose had demonstrated an overwhelming persistency to cause all his opponents to fight his kind of fight. With a damaging right hand and a powerful sneak left hook, opponents were becoming wary because they knew that Becerra could capitalize on any mistake and take them out with one punch. It had been a long time since the bantamweight division had seen such a force as this devastating 23-year-old knockout artist.

On July 8, 1959 Jose prepared to enter the ring for the biggest fight of his life. In the opposite corner was bantamweight champion Alphonse Halimi, who had beaten his idol Raul (Raton) Macias 21 months earlier. Becerra had a lot of pressure on him. He wasn’t just fighting for himself—he was fighting for Mexico. To add to his pressure, in a meeting with Mexico’s President Adolfo Lopez Mateos, Jose had promised that he would bring the title to Mexico.

The title fight was held in the new Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. On hand to witness an unforgettable brawl were 15,110 spectators. The fight was action packed every second of the way.

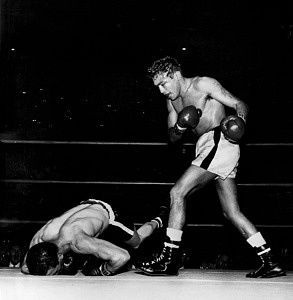

Halimi got off to a good start by taking the first two rounds with his superior boxing skills. In round three Becerra picked up the pace and tore into Halimi relentlessly. He backed the champion into the ropes where he whaled away with both hands. But Halimi wasn’t champion for nothing. He stood his ground and met Becerra punch for punch. The fight turned into a see-saw battle without let-up. The pace was terrific. Every now and then one or the other would land a hard punch that would bring the already hysterical crowd to its feet. Hopes rose and fell, but champion and challenger remained upright. It was obvious, however, that the fight was not going to go the full 15 rounds.

The end came in the eighth round.  After a minute and a half of give-and-take, Halimi hurt Becerra with a hard right to the head. But instead of backing off, Becerra came forward and exploded a left hook, followed by a right hand to the head of Halimi, sending him to the canvas. Halimi was on his feet at the count of four. He instinctively tried to protect himself. But Becerra was not to be denied. He attacked recklessly and scored with hard body punches which sapped the last remaining strength in Halimi’s body. Becerra then switched to the head and landed a beautiful left hook followed by a right hand that dropped him on his face for the full count. He didn’t move a muscle as the referee counted him out.

After a minute and a half of give-and-take, Halimi hurt Becerra with a hard right to the head. But instead of backing off, Becerra came forward and exploded a left hook, followed by a right hand to the head of Halimi, sending him to the canvas. Halimi was on his feet at the count of four. He instinctively tried to protect himself. But Becerra was not to be denied. He attacked recklessly and scored with hard body punches which sapped the last remaining strength in Halimi’s body. Becerra then switched to the head and landed a beautiful left hook followed by a right hand that dropped him on his face for the full count. He didn’t move a muscle as the referee counted him out.

Bill Miller of Ring magazine aptly summed up the emotions of the moment after the knockout when he reported: “That was when the grandfather of all demonstrations took place. Pandemonium broke loose. Frenzied fans screamed hysterically. It was contagious. Even this hardened veteran of ring activity found himself cheering. Later a friend of mine, sports-writer of a Spanish daily published in Los Angeles, told me that he had a wire from Guadalajara, Becerra’s home town – a city of 400,000 – that the city had gone stark mad. Thousands of people crowded around radios and when they heard about the first knockdown, people started to embrace each other and weep for joy. When the end came – well, try to picture it: You’ve seen Mexican fans!”

Similar excitement took place in Mexico City, where a few days later Jose received a hero’s welcome.

Tragedy struck Jose on October 24, 1959 in his hometown of Guadalajara. Jose was making his first start as champion in a non-title fight against Walt Ingram. Jose was battering the gallant and brave Ingram so badly that the referee stopped the carnage in the ninth round. While the fans were acclaiming Jose’s victory, the unfortunate Ingram suddenly collapsed. He was rushed to a nearby hospital where he succumbed to the injuries.

Tragedy struck Jose on October 24, 1959 in his hometown of Guadalajara. Jose was making his first start as champion in a non-title fight against Walt Ingram. Jose was battering the gallant and brave Ingram so badly that the referee stopped the carnage in the ninth round. While the fans were acclaiming Jose’s victory, the unfortunate Ingram suddenly collapsed. He was rushed to a nearby hospital where he succumbed to the injuries.

On December 12, 1959 Jose had his first fight since the tragic fight with Ingram and won a ten round decision over Frankie Duran in Nogales, Mexico. He wasn’t nearly as aggressive as his previous fights and appeared to hold back after maneuvering Duran in position to land one of his thunderous shots. Still he won rather handily. With a title rematch set for February against former champion Halimi, his handlers knew he would have to show a lot more intensity than he displayed in the Duran fight if he hoped to retain his title.

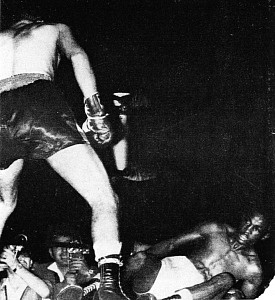

The Becerra-Halimi rematch took place on February 4, 1960 at the Los Angeles Coliseum before a crowd of 31,830. The fight was shifted from its original local when it became apparent that the arena would not hold the thousands who applied for tickets. Becerra was now the most popular fighter to ever come out of Mexico. Halimi came out for the first round intent on boxing from long range where he had the advantage. He clearly took the round with his clever boxing. The second round was following the pattern of the first round when Alphonse caught Jose with a body punch and floored him for a one count. After the second round, Jose, as was the case in their first match, started to successfully trap the challenger along the ropes. But Halimi had learned from his first encounter with Becerra. Whenever Jose tried to get inside, Alphonse either used his speed to get out of harm’s way or tied the champion up until the referee ordered them to break. The fight turned into another tense and exciting affair but through the first six rounds Halimi clearly had the edge. He was out boxing Jose in every round and also able to successfully trade punches with him when pinned on the ropes.

In the seventh round Halimi was starting to show signs of fatigue for the first time from the torrid pace. Although he was still clearly out boxing the champion he did take a number of punishing left hooks to the head. In the eighth round Halimi missed a long left and before he could get set again, Becerra caught him with two beautiful left hooks that nearly dropped him. At the end of the eighth round Halimi’s corner pleaded with him not to mix it up with the champion. They implored him to box and keep the fight at long range. But Halimi didn’t listen to his corner. He was winning the fight with his combination boxing and slugging and apparently had no intention of changing tactics. Becerra’s handlers were telling him that he was behind in the scoring and that he needed to step it up or he was in danger of losing his title.

Becerra rushed from his corner to start the ninth. Halimi tried to catch Becerra with a right hand but missed. Becerra countered with a terrific right to the heart that caused Halimi to wince and followed with a left hook with full leverage that caught Halimi on the chin and dropped him flat on his back for the full count. Nat Fleischer, editor of Ring, reported from ringside. ”Mexico has furnished many top ringmen to the fistic world but none more popular than Jose Becerra, world bantamweight champion. Striking with the deadliness of a cobra, the Guadalajara fighter, in a dramatic finish, retained his world crown by stopping challenger Alphonse Halimi, in 48 seconds of the ninth round. One well placed left hook that crashed against the jaw of the challenger stiffened Halimi’s neck and dropped him like a log on the canvas where he was counted out. Ahead on points on the score cards of all officials and most of the writers, Halimi was well on the road to regain his throne. Then suddenly like a flash, one thunderous smash that came as a shock to the Frenchman’s many rooters, crashed Halimi’s margin and ended a contest that was replete with thrilling fighting and a dramatic ending. Becerra’s single punch momentarily held the crowd, consisting of more than half Mexican rooters, spellbound. Then with a sudden explosion came a roar of ‘Viva Becerra,’ a rush for ringside, the overturning of chairs, and sombreros tossed in the air as the Mexican fans gave vent to their enthusiasm. Pandemonium enveloped the stadium as the Becerra supporters rushed pell-mell all over the arena. It was a sight to behold!”

Becerra rushed from his corner to start the ninth. Halimi tried to catch Becerra with a right hand but missed. Becerra countered with a terrific right to the heart that caused Halimi to wince and followed with a left hook with full leverage that caught Halimi on the chin and dropped him flat on his back for the full count. Nat Fleischer, editor of Ring, reported from ringside. ”Mexico has furnished many top ringmen to the fistic world but none more popular than Jose Becerra, world bantamweight champion. Striking with the deadliness of a cobra, the Guadalajara fighter, in a dramatic finish, retained his world crown by stopping challenger Alphonse Halimi, in 48 seconds of the ninth round. One well placed left hook that crashed against the jaw of the challenger stiffened Halimi’s neck and dropped him like a log on the canvas where he was counted out. Ahead on points on the score cards of all officials and most of the writers, Halimi was well on the road to regain his throne. Then suddenly like a flash, one thunderous smash that came as a shock to the Frenchman’s many rooters, crashed Halimi’s margin and ended a contest that was replete with thrilling fighting and a dramatic ending. Becerra’s single punch momentarily held the crowd, consisting of more than half Mexican rooters, spellbound. Then with a sudden explosion came a roar of ‘Viva Becerra,’ a rush for ringside, the overturning of chairs, and sombreros tossed in the air as the Mexican fans gave vent to their enthusiasm. Pandemonium enveloped the stadium as the Becerra supporters rushed pell-mell all over the arena. It was a sight to behold!”

Jose engaged in two non-title fights before defending his title for the second time on May 23, 1960 in Tokyo, Japan against Kenji Yonekura. Jose retained his title by a close split decision. The fight resembled a track meet as Yonekura kept retreating, slipping punches and occasionally lashing out snappy lefts to the champion’s face. Becerra was the aggressor throughout and kept the pressure on for the full 15 rounds. Many of his punches were short of the mark, but he landed enough to sway two of the three officials.

On August 12, 1960 Jose knocked out veteran Chuy Rodriquez in four rounds of a non-title fight in Tampico, Mexico. Eighteen days later on August 30, 1960 Eloy Sanchez shocked the world as well as Jose when he kayoed the champion in the eighth round of their non-title fight in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Jose retired immediately after the fight.

There was much speculation about Jose’s abrupt retirement from the ring. Some believed he quit because of his loss to Sanchez. Others believed that Jose lost much of his fire after he killed Walt Ingram. They pointed to the fact that his vaunted left hook had been coming across with less assurance since the Ingram fight. And then there were rumors that he retired because of eye problems. The rumors were never substantiated, and Jose was too much a man to retire over a knockout loss. The feeling here is that Becerra retired because he just lost the fire in his belly for fighting after the Ingram tragedy. Jose was a humble man who came from a deeply religious family and never sought the adulation of the crowds that most fighters miss when their fighting days were over.

So like his idol Raul (Raton) Macias he, too, walked away from the ring at the age of 24. Although he remained retired, he did return for one fight on a special benefit show in Guadalajara, Mexico on October 13, 1962, outpointing Alberto Martinez in a six rounder. The win brought his final ring record to 70-5-2, with 42 kayos.

After boxing, Jose opened an electronic repair shop in Guadalajara, Mexico. He also invested his money in restaurants and apartment buildings, but eventually lost them to mismanagement. As he entered in his seventies he suffered from an assortment of physical ailments, but kept his mental faculties. His health issues were eased by a grant from the Telemex-Tercel Foundation, Mexico’s leading philanthropic organization. On August 4, 2016 his health situation worsened and he finally passed away on August 6, 2016 at his home in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. He was eighty years old.

He was elected to the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1996, but has been shunned to date by the voters for the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Original article written in September 2000- updated August 7, 2016.