By Robert Soderman (June 27, 2000)

Published in IBRO Journal 67, September 22, 2000

Another book about Jack Dempsey has recently been published. This one is a late 1999 effort titled: “A FLAME OF PURE FIRE – JACK DEMPSEY AND THE ROARING 20S”. The author is Roger Kahn, whose previous best-selling books were primarily on baseball; including his 1972 classic, “The Boys of Summer”.

Kahn’s book about Dempsey is published by Hardcourt Brace & Company, New York, and runs to an impressive 474 pages; including the index and a bibliography, plus a prologue and epilogue. Kahn’s bibliography includes a listing of eighteen newspapers, that he supposedly consulted in research for his book. His newspaper list included the usual New York City papers (seven, with the New York Times), the Chicago Tribune, the San Francisco Chronicle and two Toledo, Ohio newspapers. (Of interest here – none of the books written about Jack Dempsey, including Roger Kahn’s, seem to have consulted the San Francisco Examiner, the Hearst paper. Why? The Examiner in Jack Dempsey’s early career years was a very interesting paper and included a great sports writer, Warren Brown on its staff. Brown was well acquainted with both Dempsey and his manager Jack (Doc) Kearns; and had a great chapter in his 1946 book, “Win, Lose, Or Draw”, entitled: “Dempsey Meets Kearns”. The reason, perhaps, was given by Stanley Walker in his 1934 book, “City Editor”: “There is a resentment against any paper which Hearst publishes, no matter how good it is.”)

However, Roger Kahn does not list two newspapers that are vital to any research into the early career of Jack Dempsey: the Salt Lake Tribune and the Oakland Tribune. The Salt Lake newspaper has to be considered a must, in carrying out any research on Jack Dempsey’s 1914 thru 1916 fights. In 1916, other than three New York City fights, Dempsey fought thirteen times in the Salt Lake area, three times in Nevada and once in Colorado.

Of Jack Dempsey’s dozen fights in 1917; four were fought in Oakland, three in Emeryville, four in San Francisco, and one – the first of that year – was the historic contest on February 13, 1917, in Murray, Utah. His first three of his eleven California fights took place in Oakland and his next two were fought in Emeryville; a town about ten miles north and west of Oakland. In 1917, Oakland and Emeryville were hotbeds for boxing, in the days of the four round bouts in the state at that time; more so than in the bigger city across the bay – San Francisco.

In regard to Roger Kahn’s book – he likewise, not being considered an expert on boxing, made several mistakes regarding his boxing facts. A principal error made by Kahn, relying on his interviews with Jack Dempsey, and Jack’s recollections forty and more years after; said that after the July 4, 1919 fight in Toledo, when Dempsey took the title from Jess Willard – Dempsey and Kearns were “broke” and had no money.

However, if Kahn had looked at microfilm for the New York Times for July 7, 1919, he would have perhaps noted a story out of Toledo of July 6, telling of Jack Dempsey squaring his account “with the man who discovered him, A.J. Auerbach, a business man of Salt Lake City”. It was Auerbach, the Times story went on to say, “who first took an interest in Jack four years ago and helped him financially to get his start on his pugilistic career”. On the evening of July 5, the Times said: “Dempsey handed over to his benefactor $6,126.20, the giant killer’s original debt plus interest, and also Auerbach’s expenses on the two weeks’ vacation he took to come here and see his protégé win the highest honors in the boxing world”.

In light of the above, this puts a shadow of doubt on the recollections of Jack Dempsey that he was “broke” after the Willard fight. Maybe Jack meant he was “broke” after presenting the $6,126.20 check to his benefactor. Also, in all the books written about Jack Dempsey, this writer has never seen any reference to Mr. Auerbach, I have not checked the list of names in all the indexes, in all the books about Dempsey; but the few I did check did not list the name of A.J. Auerbach (not Professor Bruce Evensen, Roger Kahn or Randy Roberts).

Another Roger Kahn item in question is his reference to Dempsey being approached in 1918, in Chicago, by gangster Al Capone. This item has to be taken with a few grains of salt. In 1918 Al Capone was far from being the kingpin of gangsterdom in Chicago. The big men in the gangster world in the Windy City then were Big Jim Colosimo and Johnny Torrio. In 1918 Al Capone was small potatoes compared to the big men. (However, Colosimo was murdered in 1920 and Torrio was almost murdered in 1925; and turned over the gangland empire to Al Capone in 1925.) In any event, if Roger Kahn was relying on Jack Dempsey’s recollections some 40-50 years later, memory years after the fact sometimes forgets. As author Al Stump, in his biography of baseball legend Ty Cobb, wrote: “The memories of elderly men are notoriously fallible”.

Yet another book, not entirely devoted to boxing, was authored by a man who was intimately involved with Jack Dempsey in the years 1916 to 1927. This book, “With the Gloves Off”, by Teddy Hayes; published in 1977, by Lancha Books (Texas) is subtitled: “My Life in the Boxing and Political Arenas”. Teddy Hayes acted as a trainer for Jack Dempsey in his halcyon years as world champion. Hayes’ book is listed as one of the books in Roger Kahn’s bibliography, and is also listed in the book by Professor Evensen.

Teddy Hayes’ book does mention Dempsey’s benefactor, A.J. Auerbach – the only book that appears to do so – but what Hayes has to say is at considerable odds to what the New York Times said in regard to Auerbach, on July 7, 1919.

On page 20 of Hayes’ book, and like Kahn and Evensen in their books, way off the mark in terms of factual truth; Hayes wrote: “I didn’t talk to Jack (Dempsey) that night (in 1917?), but I found the promoter, Auerbach, and I asked what the hell was Dempsey doing fighting Flynn? (Fireman Jim Flynn – on February 13, 1917, in Murray Utah.) Flynn had just been knocked out by Jack Johnson in New Mexico (Teddy Hayes’ memory is really failing him here. The Jack Johnson knockout of Fireman Jim Flynn took place four and one half years before, on July 4, 1912,) and was angling for a fight with Jess Willard, the new champion. (except, Hayes had his facts miserably twisted. Jess Willard had defeated Jack Johnson in 1915; and could not be considered a “new champion”. But, continue with what else Teddy Hayes was recollecting.)

“Finally, Auerbach admitted to me that Jack (Dempsey) was getting $500 to take it on the chin. The fight was fixed.” There have been several other assertions that the 1917 fight between Fireman Jim Flynn and Jack Dempsey was decidedly “in the bag” and that Dempsey was paid in advance to take a dive.

In Roger Kahn’s book, Dempsey said he took the bout even though his right hand was hurt and he was a one-handed boxer up against an old pro, and Flynn “punched him silly within two minutes.” Dempsey’s then wife, Maxine Cates, told another story, as mentioned in Kahn’s book: “The truth” she said, was that Dempsey threw the fight. “They offered him more to lose than to win and he took it.”

This is a subject that countless juries have haggled over for more than 80 years, and will probably dispute for another 80 years. Later on we can come back to this controversy and see what the other Boswells of Jack Dempsey wrote on this.

First let’s go back to another point that Teddy Hayes made in his book, and referred to in Kahn’s book. This subject is about Jack Dempsey’s second wife, the silent screen leading lady, Estelle Taylor; who went on to make movies into the 1930s, with one final screen appearance in 1945. Jack and Estelle Taylor were married in 1925, and divorced in 1931.

Hayes wrote that Estelle had been fired by Paramount Pictures Walter Wanger; as a consequence – supposedly – of Estelle Taylor’s then “hot romance” with Jack Dempsey. Hayes was off the mark again, in that Estelle Taylor went on to appear in Paramount films into the year 1927. And these films were big ones, albeit silents: 1924’s “The Alaskan”, co-starring with Thomas Meighan; 1926’s “Don Juan”, starring John Barrymore; and 1927’s “New York”, co-starring with Ricardo Cortez.

According to Teddy Hayes, Dempsey had just finished his Universal Studios series called, “Fight and Win”, and Teddy arranged for a celebration party at Hollywood’s Montmarte Club. A ringside table for four had Dempsey and Taylor, with Hayes, awaiting the arrival of Doc Kearns; who arrived in a state intoxication and nastiness.

Kearns had investigated Estelle Taylor’s past, and her previous amours; one of whom “had paved the way for her to get into movies.” Kearns soon got into a shouting match with Hayes, who had been a production manager for Dempsey’s “Fight and Win” films. “You’re suppose to have been in charge of production. What’s going on around here. What the devil have you been doing?”

Hayes tried to calm Kearns down. “Keep your voice down, Doc. We’ll talk about it later.” Kearns resented the influence Estelle Taylor was beginning to have on Dempsey, and wanted her to get out of the way.

Estelle chimed in by saying that with all the publicity her romance with Dempsey was getting, she thought it would be a good thing if the two of them could be starred in a feature film; and she had a screen play in mind called “Manhattan Madness”. Doc Kearns interjected by asking what she was going to do for money, and Estelle said, “Oh, you boys can take care of that, and we could get Paramount to release it.”

According to Teddy Hayes, Kearns wasn’t buying it. “The public wants to see Dempsey fight, not make films. So to hell with your movie”, yelled Kearns.

Estelle Taylor had had enough and ordered Dempsey to fetch her opera cape. In an instant they headed for the door. They took a cab to Estelle’s home, with Teddy Hayes following in another cab. As Hayes got to the house he could hear Estelle giving Dempsey an earful. “You let that drunken slob insult me. I don’t want to hear another word about that man”.

Hayes tried to act as peacemaker but Dempsey, siding with Taylor’s tirade, said: “No, Ted, it’s all over. I’m through with Doc. I’ll go my own way if I have to.”

That was in 1924, before Jack and Estelle married in 1925; and was the beginning of the end of the partnership between Jack Kearns and Jack Dempsey. For the next few years, according to Teddy Hayes, it was Estelle who was advising Dempsey in his dealings with Tex Rickard, and as to who his 1926 opponent was to be.

The array of books about Jack Dempsey over the span of years, offered a variety of versions about that historic February 13, 1917 knockout defeat in Murray, Utah at the hands of Fireman Jim Flynn. There were virtually no results of this bout that appeared in any newspaper east of the Mississippi River; not in the Chicago Tribune or the New York Times. After all, no boxing fan outside of Utah, Nevada or Colorado had ever heard of Jack Dempsey.

The Pueblo, Colorado Chieftain, in their edition of February 14, 1917, under the date of February 13, did report on the Dempsey-Flynn fight; and devoted three lines to their account. “Jack Dempsey of Salt Lake City was knocked out in Murray a suburb of Salt Lake, tonight by Jim Flynn of Pueblo ten seconds after the men shook hands. Flynn pushed down Dempsey’s guard with his right and swung his left to the jaw. The Salt Lake man sank to his knees and over for the count and it was 20 seconds after Flynn had been declared the winner before Dempsey regained his feet.” The headline over the small report said: “Dempsey Loses to Jim Flynn in First Round”.

The Oakland Tribune, in their edition of February 14, 1917, ran a one – sentence report under the headline: “Flynn wins in ten seconds”; and ran the first line of the story that also appeared in the Pueblo Chieftain.

The Salt Lake Tribune, in their day of the fight report was headlined: “Flynn and Dempsey Will Step Tonight”. Their lead paragraph said: “With Frank Armstrong named to referee and both boxers in the best of condition, Promoter Fred Winsor announced that nothing remains incomplete in the arrangements for the Jim Flynn – Jack Dempsey fifteen round fight bout at Murray tonight”.

Two things to note here – the promoter is Fred Winsor; who would later in 1917 become Jack Dempsey’s manager, and that the fight was to have been a fifteen round contest, the first time in his career that Jack Dempsey was to go that distance.

The Salt Lake Tribune’s story elaborated on the efforts Promoter Winsor had arranged in behalf of the fans who would attend his promotion. The largest crowd ever to be on hand for a Murray fight show was expected, and “the street car company has made arrangements to run extra cars before and after the bout.” In addition, special trains would come from Bingham, Payson and Provo; and Promoter Fred Winsor was “especially anxious to get the out-of-town fans back to their special trains as soon as possible at the conclusion of the evening’s Program.”

The prefight story also had a few words from Jim Flynn, who said: ” I wish I could be as positive of everything else in the future as I am that I am going to win this battle.” Flynn was so sure of victory that he was ready to back up his belief with a wager on himself. “That’s gotten to be my business of late – teaching these young fellows boxing lessons,” he concluded.

Dempsey, the Tribune story said, is not inclined to boast, but considers himself faster than Flynn and as having a better punch, and therefore he is not worrying about Flynn’s attack.

However, the prefight story had another, important sentence to impart to its readers: Billy Roche, representing Flynn, and A.J. Auerbach, Dempsey’s manager, got together yesterday afternoon and agreed upon Frank Armstrong to officiate and give the decision.

The result story the next day had a bold headline over its story: JACK DEMPSEY FLATTENED OUT IN 25 SECONDS. The sub headline wasn’t too subtle either: “Jim Flynn Makes Quick Work Of It At Murray; Local Man is Unprepared For Onslaught.” The story went on to relate all the terrible details. “Jack Dempsey of Salt Lake lasted about twenty-five seconds in his match with Jim Flynn of Pueblo last night at Murray.

“During those twenty-five seconds, ” the Salt Lake Tribune’s writer said, “Flynn punched Dempsey twice on the right side of the head, twice on the left side, broke down Jack’s guard with his right and put the finishing touches on with a steaming wallop with his left to the jaw. Dempsey was out about half a minute.”

The Tribune made an excuse of sorts for Dempsey’s poor showing. “Those who have seen Dempsey fight have always admired his ability to take punishment, but usually the punishment came in the course of a battle, and to have it come all at once, like a bolt of lightning, was too much for the local scrapper.”

Nowhere in the source of the Tribune’s account was there any mention of any punches thrown by Jack Dempsey. “During the few seconds the fight lasted, Flynn made two attacks. At the beginning he bent his head downward and bored in, whaling away with both hands. Then there was a wee bit of a lull, during which the referee tried to do some separating and next came the onslaught with its two-blow finish.”

After the last preliminary bout, the Tribune writer said, “the spectators settled themselves back for the main event. Then they unsettled themselves, because the main event didn’t show up. For forty-five minutes the fans who had paid from $2 to $5 for seats waited with noisy impatience.” And now came a very important statement in the Tribune’s result report; one that, in later perspective, sheds a great deal of light in illuminating some historical background.

“The delay, ” said the Tribune, “it developed later, was due to financial arguments in the box office.” Financial arguments, indeed! In light of later developments, and recollections by three Salt Lake men who were at the fight; we can make a few guesses as to this financial confab that delayed the main event by forty-five minutes. Most likely the discussion, or the arguments, involved the managers of the fighters; Billy Roche, for Jim Flynn, and A.J. Auerbach, for Dempsey.

Jim Flynn didn’t tarry in Salt Lake after the fight, leaving to fill dates in the South and East. Jim’s next bout was on March 20 in New York City, where he took a ten round shellacking from Bob Devere. Jack Dempsey wouldn’t fight again until March 21, in Oakland, California, where he fought a four round draw with highly regarded coast heavyweight Al Norton.

Compare this Salt Lake Tribune ringside report on this historic February 13, 1917 fight, to the several different versions of what supposedly happened; in the various books written about Jack Dempsey. In virtually all of these books, the telling of what happened in this bout, came from Jack Dempsey himself. Not one of the books verified Dempsey’s several versions against the actual newspaper report in the Salt Lake Tribune.

Jack Dempsey’s previous fight in Salt Lake had been on October 16, 1916, when he had won a ten round decision over Dick Gilbert, the Louisville, Kentucky heavyweight. On this occasion the Salt Lake Tribune writer had a lot of praise for Dempsey – “Local Pride Fights Clever Mill From Start to Finish”, was a sub-headline over the result story. “Jack Dempsey, the local pride and the peer of any light heavyweight on the coast, gained a well-earned decision over Fighting Dick Gilbert of Louisville, KY., last night at the Salt Lake Theatre. A crowded house was treated to a series of contests enough to satisfy the most fastidious.”

The Tribune writer didn’t think too much of the first six rounds – “there wasn’t much shown in the way of science, it being a case of slam-bang, wrestle, clinch, back away and then the same thing over again.” Things changed starting in round seven, according to the Tribune’s result story. “Dempsey showed his superiority and soon had the Louisville terror floundering about the ring, which floundering continued until the end”. The story did not ignore Dick Gilbert’s efforts, saying “Dick’s best was at infighting, anticipating that Dempsey’s innards would not stand a merry tattoo. While he landed quite a few in the stomach, the local boy never backed up and at the end was the fresher of the two. Referee Hardy Downing’s decision met with the approval of everybody present.”

Note the name of Referee Hardy Downing, who was also the promoter. The referee for the preliminary bouts was Jack Price, who accompanied and managed Dempsey for his contests in New York, earlier in 1916. The Tribune also mentioned: “The handling of the large crowd reflects great credit on the management of the club. Many women were present in the audience, and seemingly got as much enjoyment out of the bouts as their escorts.”

Now just who was “Fighting Dick” Gilbert? According to his record in the 1943 All-Time Ring Record Book, he had been fighting since 1907 and had fought such ring luminaries as Battling Levinsky (four times), Tom McMahon, Leo Houck, George Chip, Jack Dillon, Gunboat Smith, Al Norton, Billy Miske and Bob Moha. That record book lists 109 total bouts for him, up to the bout with Jack Dempsey.

Dempsey would have one more 1916 bout, a knockout win over Young Hector, at Salida, Colorado, on November 29; before his bout versus Jim Flynn, the Pueblo Fireman.

In the September 1933 issue of Ring Magazine, a writer named Harvey Bright authored an article titled:”THE MAN WHO KAYOED DEMPSEY” and sub-headlined the phrase: “Recounting The Ring Exploits of Jim Flynn, The Pueblo Fireman, Who Put The Only Blot On The Manassa Mauler’s Escutcheon.” The article told of the ring career of the “Pueblo Fireman”; but started with the memorable encounter on February 13, 1917 in what the article said took place in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“The end came in the very first round, ” said Harvey Bright’s article. But, Bright didn’t offer any details of this “memorable encounter”; merely saying: “many of the ringsiders were of the opinion that it was one of “those things”. Dempsey’s friends have always insisted that Jack “took a dive”.

Bright’s article used Dempsey’s own one round win over Jim Flynn a year later – in 1918 – as substantiating the “dive” aspect of the first meeting of Dempsey and Flynn. Dempsey himself, Bright went on to say, “has often said that he was broke, and didn’t try to beat Flynn, for at the time he was only a novice and was out to make a few dollars, but the fact remains that Jack was knocked out – the only K.O. chalked up against him in his entire career.”

Perhaps the earliest book about Jack Dempsey that told the story of that February 13, 1917 fight, was in the first of many books about the “The Manassa Mauler; Nat Felischer’s “Jack Dempsey, The Idol of Fistiana”, published in 1929. The many books that followed, the 1960 “Dempsey, By The Man Himself”, as told to Bob Considine and Bill Slocum; “The Long Count”, in 1969, by Mel Heimer; Randy Roberts’ 1979 book, “Jack Dempsey – The Manassa Mauler”; and Nat Fleischer’s second book, his 1972 “Jack Dempsey” – all gave various versions of what supposedly really happened in Murray, Utah, on February 13, 1917.

The 1960 Dempsey, Considine, Slocum book had this version; …”My next manager turned out to be a fellow I had known a little in Pueblo, fellow named Fred Windsor (sic) (the last name is really WINSOR; but it seems that every book ever published on Jack Dempsey spells FRED WINSOR’S name as Fred Windsor.), called Windy, which he was. I was still trying to heal my busted fingers when I got a wire from him, asking me if I wanted to fight Jim Flynn in Murray, Utah. Wire collect, one way or the other, he asked me.

“Fireman Jim Flynn, as they called him, was rated right up there with Gunboat Smith, Carl Morris, Frank Moran and Bill Brennan. As I read and reread the telegram I got some of the feeling I had had in New York when John the Barber (Reisler) kept trying to push me in there against Langford. But the more I thought about Flynn the more I thought about Carl Morris, who was considered his equal. I didn’t think I could lick Flynn but I knew damned well I could beat Morris, just because I was so burned up over that eighty-nine cents – or the principle of the eighty-nine cents, so I wired Windy “okay”.

“About four hundred fans showed up the night of the fight to see one of the most famous fights of my life. Flynn knocked me out in two minutes of the first round. (But, see wire service report out of Salt Lake City, February 14, 1917, which read: “Jack Dempsey of Salt Lake City was knocked out at Murray, a suburb of Salt Lake City last night by Jim Flynn of Pueblo, Colo., ten seconds after the men shook hands.”) (Also, see story in the Oakland Tribune, which appeared on Friday March 16, 1917; and gave Jack Dempsey’s own version of the one-round knockout defeat at the hands of Jim Flynn. The wire service report of February 14 also was in the Oakland Tribune.

“It was the only official knockout of my prize-fighting career.

“In the first minute of the fight he hit me with a right that put me on the deck. I came up groggy and he was waiting there over me, and down I went again when he hit me. I got up and this time I was able to hold. But only for a few seconds. He knew how to get out of a clutch like that. He broke away, stepped back, threw a punch, and I was flat on my back a third time. When I got up I couldn’t see him. He was behind me. I turned like a drunk, I guess, and he let me have it while my eyes were trying to find him. I went down again.

“As I got up to face Flynn, my brother Bernie, working in my corner, threw in the towel. When the fogs went away I cussed him, my own brother. ‘Why? Why? Why? I kept yelling at him. Bernie was a pro. He was right. He didn’t stop it because I was his brother; he stopped it because I was having my brains beaten out.”

Nat Fleischer’s 1971 book had yet another version: “After he (Jack Kearns) and I had joined in partnership, my rise in the fight world definitely got under way. A fight I lost before he became my manager was with Jim Flynn in Murray, Utah, February 13, 1917. That’s when the bout was halted in the opening round. I’ve heard it said that I went into the tank for that fight, but it’s not true. What happened was that Flynn hit me with a power punch that shook me up. I didn’t have any real pro handler in my corner. My brother was taking care of me again, and as is usual in such cases, he thought I was badly hurt, got scared, and tossed the towel into the ring. That’s the true story. I could have continued if he had not interfered.”

Mel Heimer’s 1969 tome had a few words to describe his interpretation of what happened: “Jack kept scrambling, changing managers as if they were dirty shirts. One of them, Fred (“Windy”) Windsor (again, Windsor instead of WINSOR), matched him in Murray, Utah, with “Fireman” Jim Flynn, a “cutie” (who knew all the tricks of the ring). Dempsey, whose fingers were still healing from an injury, was knocked out in two minutes. His brother Bernie, working as his second, tossed in the towel after four knockdowns. “He’d had killed you with another punch, ” Bernie said apologetically. It was the only official knockout of Dempsey in his career.”

Randy Roberts’ 1979 effort had the briefest explanation of all – just two sentences: “The fight did not take long. Flynn knocked Dempsey down several times and before the bell rang to end the first round, Dempsey’s brother Bernie, who was acting as his manager, wisely threw in the towel. For the first and only time in his life, Dempsey suffered a technical knockout.”

Randy Roberts’ book lists the newspapers he consulted – 28 in all. The usual “big city” newspapers: Chicago Tribune and New York Times are listed; plus others off the “beaten” research track: Baton Rouge, London Times, Manchester Guardian, four in Omaha, Opelousas, St. Louis, Toledo and San Francisco. However, it seems that Roberts did not consult Salt Lake City, or Nevada, or Colorado newspapers, whatsoever. Also, Randy Roberts makes the mistake of referring to Fred Windsor – instead of him giving his correct name of Fred WINSOR.

Nat Fleischer’s 1929 book, seemingly the first ever book about Jack Dempsey, that Nat titled: “Jack Dempsey, The Idol of Fistiana”, and published by Fleischer’s Ring Magazine; was published in a paperback edition in April 1949 by Bantam Books. It is doubtful if Nat did much research – especially in regard to Jack Dempsey’s early ring career – before writing his book.

In terms of what Fleischer had to offer about the February 13, 1917 bout with Jim Flynn; all Nat wrote was one paragraph on his page 4, with just one sentence in that lone paragraph of the Jim Flynn fight. Fleischer’s sentence merely said: “In the following year (1917)….he suffered a questionable one round knockout by Jim Flynn, Pueblo Fireman, but subsequently reversed this setback.”

In defense of Nat Fleischer – in 1929 when he wrote this book – there were no newspapers on microfilm, anywhere in this country. Libraries maintained stack – on – stack of newspapers in their towns, accumulating daily, for all the years in the past; even in towns or cities such as Salt Lake City, Pueblo, San Francisco or Chicago and New York City. So, in order for Nat Fleischer to have researched those early 1916 and 1917 fights for Jack Dempsey, he would have had journey from New York to Salt Lake City to examine – personally – those by then crumbling and yellowing daily newspapers. The use of microfilm was begun in 1928 for banking purposes. It wouldn’t be for several more years before someone had the bright idea to put all those library – held – stacks of old newspapers on film – microfilm – freeing up mountains of library space in libraries all over the country.

One other book, not strictly devoted to Jack Dempsey; but, rather to his dynamic manager, Jack (Doc) Kearns, was the 1966, “The Million Dollar Gate”. This was by Jack (Doc) Kearns as told to Oscar Fraley, and publicized by the MacMillan Company. “Well, I saw him box Al Norton or somebody in Oakland (Eddie Kane, a friend of Kearns is talking.), and he looked like he might be a helluva fighter,” Kane recalled. “He wasn’t in shape and he got tired. But he looked like he might be all right. I hear he got flattened in one round in Salt Lake City by Jim Flynn, but it was suppose to be one of those things.” Kane’s wink told me that Dempsey might have taken a dive in the interest of a quick payday.

“What I learned later certainly seemed to substantiate this theory. Dempsey, on his return to Salt Lake City, had gotten a job as a saloon bouncer and had fallen in love with a girl named Maxine Cates, a piano player. She was somewhat older than he was, but they were married in Farmington, Utah on November 9, 1916.

“The romance bounced along a rocky road. They were destitute. Maxine warned Dempsey that if he didn’t come up with some money, and quickly, she was going back to work, one way or another. So Jack took the bout with Flynn, known as the “Pueblo Fireman”, and was knocked out in the first round.”

Another version of Flynn-Dempsey was related in the July 1969 issue of International Boxing, complete with a full color cover featuring Jack Dempsey and a scene of his win over Jess Willard in 1919. The entire issue – 65 pages – was devoted to “The Jack Dempsey Story – 50 Years A Champion”, written by Bob Waters and Stanley Weston. Their version: “Jack was in Jackson’s gym in Salt Lake when he received a telegram from a promoter in Murray, Utah, offering him $250 to fight Fireman Jim Flynn. It was an invitation to commit suicide….Jack climbed into that ring at Murray, Utah, with the confidence of a man who had just gotten married to Maxine Cates, who played the piano in a Salt Lake saloon on Commercial Street.

“Watch his right, “brother Bernie warned, “it can kill you”. “Don’t worry, Jack supposedly replied, “I’m going take this old man (Flynn was 37) out and fast.” Dempsey feeling all the juices of his youth and stamina, walked cockily to the center of the ring. He flicked a left at Flynn, danced a little and started another flicking left. It never landed. Flynn’s right hand caught Dempsey flush in the face and Jack went down like a chimney, a little bit at a time. Dempsey tried to cover up and hold when he got up, but Flynn’s experience wouldn’t allow that. Flynn hammered two lefts into Jack’s ribs which straightened the boy from Manassa and another right put Dempsey down again.”

“Twice more Jack got to his feet, and there was nearly a minute to go when brother Bernie threw in the towel,”

A wire service story out of New York, dated June 30, 1923, appeared in the Arizona Republican of July 1, 1923. This was part of the publicity generated by the upcoming July 4, 1923 fight between Jack Dempsey and Tommy Gibbons, in Shelby, Montana. This story was headlined: “Dempsey Was Poor Prospect When He First Entered Ring”. A few paragraphs into the article it said: “Early in 1917, after a series of exploits by no means brilliant, Dempsey was knocked out in one round by Jim Flynn, the Pueblo Fireman. Various reports were circled about that fight and later Dempsey redeemed himself by disposing of Flynn in less than a round.”

The short article – nine paragraphs long – went on to say: “While Dempsey’s early performances were mediocre and suggestive of anything but future greatness, he developed into one of the greatest heavyweights in ring history.”

The Oakland Tribune, in their edition of Friday March 16, 1917, was highly laudatory of Jack Dempsey; even though he had yet to appear in an Oakland ring. The Tribune’s story was headlined: “Dempsey Wakes Up West Oakland”. The underneath headline said: “Salt Lake Heavyweight Is The Fastest Man Here Since Harry Wills.” (Note- Wills had fought six bouts in San Francisco, in 1914; scoring three knockouts and winning three four-round decisions, one of which was overWillie Meehan.)

The Oakland Tribune’s writer waxed lyrical over Dempsey, with their lead paragraph saying: “West Oakland has awakened to the fact that a real fighter has blown into town. The boxer who bears a blue label is Jack Dempsey, whom Fred Winsor has brought here from Salt Lake City for the purpose of showing by Al Norton at West Oakland next Wednesday evening.”

The Tribune article went on to say: “Dempsey has only been boxing for three years, and he is just twenty-two. His record shows that he beat Joe Bonds, Wild Burt Kenny, Terry Keller (sic) and Dick Gilbert. He also whipped Andre Anderson, the New York heavyweight.

But the most significant part of the Oakland Tribune’s otherwise glowing story on Jack Dempsey; came a paragraph later. Bear in mind that this story appeared on Friday March 16, 1917, well before any other description of what happened in Jim Flynn’s knockout of Jack Dempsey (on February 13, 1917). “The one blotch on Dempsey’s list of performances, “the Tribune article added, “is the fact that he was knocked out by Fireman Jim Flynn at Salt Lake. Dempsey explains this, “(Note that the story says that ‘Dempsey’ explains) “by saying that when they came into the center of the ring for the first round, he put out both gloves to touch his opponent’s mitts as is customary, and Flynn took advantage of the move to whip over a right haymaker to the jaw.” Now – compare this description of what took place, to those other descriptions related previously.

The Oakland Tribune went on to add one more sentence: “Press accounts bear out Dempsey’s story and say that the young Utah fighter really was the victim of an unprofessional act on the part of the tricky veteran.”

WHOA! HOLD ON! What “press accounts?” Not the Pueblo Chieftain. Not the Oakland Tribune. Was the story that bears out Dempsey’s so called version in the Salt Lake City papers? Was it in the San Francisco Chronicle, who most likely would have run the same wire service report as the Oakland Tribune?

It looks like we have a real mystery here. What is the true story, and which version is correct?

How about one more version? This one, circa early 1920, from a series of 23 articles run in the Chicago Tribune; from their editions of February 15, 1920 to March 8, 1920. The articles were titled: The Life And Adventures Of Jack Dempsey”; and began with a statement of purpose. “The Tribune assigned Eye Witness (sic), one of the ablest and most experienced reporters in the country, to “cover” the career of Jack Dempsey in a series of unbiased articles, first of which is printed herewith. “Get the truth”, was the only instruction given to the reporter. He is not a sporting writer, and he has approached the subject as an outsider, without preconceived opinions. He has here written a human picture of one of the most interesting and spectacular individuals in modern sporting life. The series will appear daily on the sporting pages.”

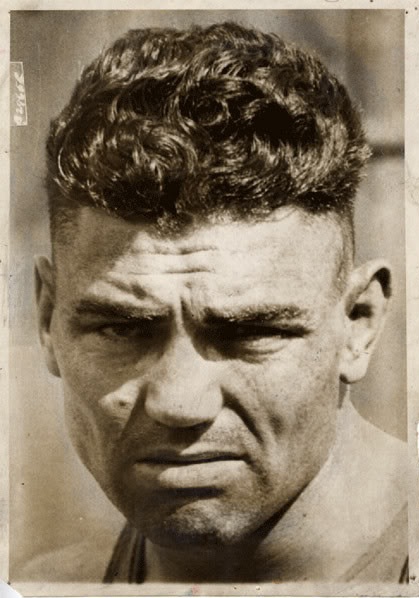

The big, bold, black headlines over the first article in the series, said: SQUALOR, DECEIT, ROMANCE, MIX IN PUGILIST’S STORY, The underneath headline read: Boxing Champion’s Life Thread Woven in Raw Traits of Humanity. The first chapter also was illustrated with the photos of various Salt Lake homes occupied by the Dempsey family.

Chapters IX, X, XI, XII, and XV gave the findings that “Eye Witness” came up with in his interviews with the Salt Lake City men, and friends of Dempsey, who told of what they knew of the now in-famous February 13, 1917 bout with Jim Flynn. Indeed, Roger Kahn in his 1999 book, mentioned the 1920 Chicago Tribune articles by the anonymous “Eye Witness” (two words, Roger; not the single word “eyewitness” you used in your book.). Roger Kahn dismissed this series by writing that the series was necessarily incomplete; but it only told of Dempsey’s life up to February 1920.

The Chicago Tribune’s” Eye Witness” obviously was of the old school of biographers, in that he felt he should get his facts on events of Jack Dempsey’s life; firsthand from the people who were there with Jack at the time. So it was when “Eye Witness” got to the part of Dempsey’s fistic life that told of the February 13, 1917 fight in Murray, Utah, between Jack and

Fireman Jim Flynn of Pueblo, Colorado.

Three men told what they knew of what took place on that memorable day. They were John Derks, sporting editor of the Salt Lake Tribune; Hardy Downing, a Salt Lake City promoter of boxing matches for seven years; and Al Auerbach, a Salt Lake City beauty parlor operator, who also was Jack Dempsey’s third manager, from early 1916 and after Jack’s return from New York in July 1916. “Jack paid the bills always,” recalled Auerbach. “Jack had dependents a plenty. He’d be training hard between those early fights and then maybe get $25 or $40, and next day he’d be broke from paying Mother’s grocery bill”.

Auerbach, the man not mentioned in any of the books written about Jack Dempsey over the next eighty years, went on to add more recollections: “Now you take the Flynn fight and all the grief it caused. That was the result of driving need, I tell you. Of course, the boy had never seen $500 of which he or the family hadn’t owed most.”

Auerbach was also the billpayer for the Flynn-Dempsey fight at Murray. He recalled his conversation some time after that fight, when Dempsey told him: “I tell you, Al, if I had my life to live over I’d never do that thing again.”

Eye witness, in his Chapter X, titled – That Fight At Murray – was headlined at the top of the article: “Dempsey’s Lone K.O. Of Career Raw Frame up.” The sub-headline said: “Needed Coin, So Flopped To Flynn”. The fight was to be for the benefit of the Murray Fireman’s Fund.

Jim Flynn, the railroad fireman from Pueblo, was still a notable name in the boxing world in February 1917, and had literally fought every heavyweight worth mentioning over the last several years. Jim Flynn had even fought Jack Johnson for the world heavyweight championship, at Las Vegas, New Mexico, on July 4, 1912, and lost on disqualification in 9 rounds; due to excessive head butting.

Flynn had fought just three times in 1916, losing twice to Jack Dillon – once by knockout – and to Fred Fulton, also by knockout. After the Fulton defeat, the Chicago Tribune’s boxing writer, Ray Pearson, wrote that Jim Flynn was nearing the end of his career as a trial horse, and that he no longer seemed able to stand up to the blows of men such as Fred Fulton. (However, Fireman Jim Flynn continued fighting into the year 1925; despite being labeled “through” by writer Pearson).

Hardy Downing got a tip that the fight was to be on the queer, and took his suspicions to the Sheriff’s office in Salt Lake. The sheriff’s people kind of stalled, said Downing, and didn’t see what they could do. “Yes, I was there at the fight,” admitted Downing. “Flynn came on fanning with both hands and Jack went into his shell. He took Flynn’s blow and went down, and as he fell put his right glove against his cheek and he did a little flopping. The clamor that night in certain Salt Lake saloons where sports foregathered was fearsome.”

In 1916 Jack Dempsey had fought fifteen times; three times in Nevada, three times in New York City, once in Colorado, and eight times in Utah. He only lost one of those bouts – the July 4, 1916 Saturday night fight, to John Lester Johnson, at New York City’s Harlem Athletic Club. In this battle, a newspaper decision ten-round loss, Jack also suffered three broken ribs. Eight of Jack’s fourteen wins in that year were knockouts, and the two New York wins were over highly rated foes: Andre Anderson and Wild Burt Kenny.

John Derks said he was at the fight in question. “In the first round, indeed, at the second blow, Flynn landed a terrific punch on Dempsey’s jaw. Flynn has a reputation for putting tremendous force into his blows, and there is no gainsaying that the blow which he delivered to Dempsey’s jaw was terrific. It developed later, “Derks concluded, “that the fight was a frame, and that to distinguish it from other frames it was agreed to end it quickly.”

So, in the early 1920, the recollections of three Salt Lake City men; all of whom knew Jack Dempsey intimately, and all of whom were present at the February 13, 1917 fight in Murray, Utah, when Jim Flynn knocked out Jack Dempsey; are all of the firm opinion that the fight was “fixed”, a “fake”, a “frame”. The three also declared to the Chicago Tribune’s “Eye Witness” – individually – that Jack Dempsey took a “dive”, for the sum of $500.

One year and one day later, on February 14, 1918, Jim Flynn and Jack Dempsey met again. This time it was in Fort Sheridan, Illinois, and Jack Dempsey knocked out Jim Flynn in the first round; the time was 1 minute 32 seconds.

A third meeting of these two, socially, took place in Phoenix, Arizona; a few days after Dempsey had knocked out Jack Sharkey in New York City on July 21, 1927. Dempsey’s train, en route to Los Angeles, had stopped off in Phoenix for a short visit. An enthusiastic crowd was on hand to pay its respect to the former world champion.

“Looking out over the crowd Dempsey saw Jim Flynn, the Pueblo Fireman who is credited with the only knockout against him,” the Arizona Republican reported.

“Hello there, Jim”, Dempsey shouted. “What are you doing here?”

Flynn edged his way through the crowd as Dempsey reached out to shake his hand. “Been a long time since I’ve seen you,” said Jack. Then followed a period of reminiscence and the Phoenix taxi operator and the titular contender had an enjoyable visit and afforded the crowd an opportunity to see the real Dempsey.

‘This seems to be a nice place,” Dempsey said with a smile.

“Best place I’ve ever been in,” Flynn replied.

It is not known if Dempsey and Flynn ever met again; but they both seemed to have the most friendly respect toward each other.

There was one more, early Boswell of Jack Dempsey, Hal Cochran, a syndicated writer; who authored a six-part newspaper series on Jack Dempsey’s career. This series appeared in the Arizona Republican, beginning Monday May 23, 1921 and ending Monday May 30, 1921. Chapter one told readers: “This story of Jack Dempsey’s career has been written for the Arizona Republican by Hal Cochran on information much of which was furnished by Dempsey himself. The rest was obtained from Dempsey’s close acquaintances and official records.”

Hal Cochran’s series told of Jack Dempsey’s early life, and early career; his partnership with Jack Kearns, and his winning of the title. It wasn’t until Chapter five, on Sunday May 29, 1921, that Hal Cochran mentioned Dempsey’s bout with Jim Flynn.

“Jack’s next bout,” Cochran wrote, “was with Fireman Jim Flynn at Murray, Utah. Dempsey was knocked out in the first round.” And, “at this time Dempsey was under the management of Fred Winsor (note that Cochran at least got Winsor’s name correct; unlike later writers.), better known as “Windy”, one of the noisiest managers in the game.”

Here again – liberty – with the facts. When Dempsey fought Flynn, his manager was Al Auerbach, not Fred Winsor; and Fred Winsor was the promoter of the infamous fight. Cochran skimmed over Jack Dempsey’s early life and career, which was aided by cartoon depictions illustrating various highlights in each of the six chapters. However, he came up with several interesting items. His second manager, Jack Price, who traveled to New York in June 1916, with Jack Dempsey; was a brother-in-law of Salt Lake promoter Hardy Downing (except-Cochran wrote the name as “Hardy Downey”).

Another set of items were the purses that Dempsey supposedly received for some of his 1916 fights. For the April 8 contest in Ely, Nevada, where he defeated Joe Bonds in ten rounds; he was paid $325. For his next fight, on May 3, in Ogden, Utah, Jack took down $350 and won the ten round decision over Terry Kellar.

On the subject of Fred Winsor – he was still managing heavyweights in 1924; hoping that he could come up with another Jack Dempsey. Fred was also the manager, at this time, of Tony Fuente; whom he had been building up on a series of quick knockout wins over third and fourth raters. On Monday, November 17,1924, at the new Culver City, California arena, where he was also the promoter, Winsor matched his heavyweight sensation Tony Fuente with the famous Minnesota Plasterer, Fred Fulton; whose first round knockout loss to Jack Dempsey in 1918 had propelled Dempsey into his 1919 title match versus champion Jess Willard.

Fred Fulton was still a heavyweight name to be conjured in 1924, and had started out the year scoring four quick knockouts. For some reason, however, he didn’t fight again until October – a six month hiatus from the ring – when he was outpointed in his native St. Paul by Martin Burke. So, the stage was set for him to become a big “name” in Tony Fuente’s increasing list of victims. Fred Winsor seems to have had a hand in persuading opponents of his fighters to be willing participants in his nefarious plans.

In less than a minute Fuente floored Fred Fulton three times, and scored a very dubious one round knockout win, On hand were 4,000 fans, including former world heavyweight champion Jim Jeffries. Many of the fans in the audience were irate, rising to their feet and yelling “FAKE! FAKE!”

The next day, Tuesday November 18, 1924, Fred Fulton and his manager, Jack Reddy, were arrested. Fred Winsor and his fighter Tony Fuente went “on the lam”, and where nowhere to be found. Shortly after, Winsor, Fuente, Fulton and Reddy were barred in California.

Go back to February 13, 1917. Fred Winsor was the promoter of the fight in Murray, Utah, when Jim Flynn knocked out Jack Dempsey; in another out-and-out “fake fight”. Fred Winsor had been skating on boxing’s thin ice for several years in California, and there had been many rumors of shady practices involving his fighters.

Of the many books written about Jack Dempsey, just about all of them seem to have relied on discussions, and interviews, with Jack Dempsey himself. An excuse can be offered for the first of these books – the 1929, “Idol of Fistiana”, by Nat Fleischer. There was no relatively easy way for Fleischer to actually research the Utah, Nevada, Colorado or California newspaper stories about Jack Dempsey’s early – 1915 to 1917 – bouts. Of course, he could have taken a train ride across the country and then taken a week or two; to visit libraries in Utah, Nevada, Colorado and California. He could then have consulted the actual newspapers in the hands of those libraries. He didn’t obviously.

The later authors of books on Dempsey didn’t either; but some of them did list some western newspapers in their volume’s bibliographies, supposedly as part of their research. These later authors would have found it far easier than Nat Fleischer in 1929. They would have been able to study newspaper microfilm of cities such as: Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Oakland, Ogden and Provo, Utah, and Elko, Nevada. Today (year 2000) letters to libraries in those, and other cities, can request specific stories from specific days of specific years, with offers to pay for photocopy and postage costs. These requests will usually bring results.

Newspapers were put on microfilm starting in 1934, by Bell & Howell Company in Chicago. This was a fabulous boon to libraries, and to historians and writers of every ilk.

The many books about Dempsey possessed other factual faults, in addition to faults in their boxing coverage. One of those non-boxing faults; but tied to boxing, was what was said in relation to Dempsey’s second wife, screen actress Estelle Taylor. She had been in silent films from 1919 to 1929, and had been a star in talking films through the early 1930s.

According to Jack Dempsey’s various Boswells, Estelle Taylor, after her marriage to Dempsey in 1925; was fading as a screen actress. On the skids, was the verdict. No studio wanted her anymore.

Here again – a modicum of devoted research, and a study of the films Estelle Taylor appeared in; give a somewhat different story. Estelle had been in over twenty silent films up to her marriage to Dempsey; and her lone film in 1926, “Don Juan” starred John Barrymore. Indeed, Estelle had second billing in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 epic, “The Ten Commandments”; and was a sensation when, “lovely, lightly-clad Taylor got a great deal of exposure during the orgy sequence as the golden calf is adored.

Taylor’s leading men in her films were: John Barrymore, Thomas Meighan, Ricardo Cortez, Lon Chaney, Richard Dix and Ronald Colman. Far from slipping as a film star in 1931, when Jack Dempsey was granted a default decree divorce in a Reno, Nevada court room on September 21; Estelle Taylor starred in a pair of memorable films in that year.

The 1931 “Cimarron” won that year’s Academy Award as best picture. Also, both leading man Richard Dix and leading lady Irene Dunne, were nominated for academy awards in the 1930-31 ceremonies; but Dix lost out to Lionel Barrymore in “A Free Soul”, and Dunne lost out to Marie Dressler, in “Min And Bill”.

If supporting actor and supporting actress awards had been given out in 1930-31 ceremonies; Estelle Taylor may well have been nominated for best supporting actress, for her outstanding role in her portrayal as schemer Dixie Lee in “Cimarron”. She could also have been nominated in that same year – if best supporting actress had been an academy category then – for her other successful film in that year; as Anna Maurrant in the powerful “Street Scene”. In this film she was shot to death by her film husband, David Landau, who in the film discovered Estelle and her screen lover, Russell Hopton, in a very compromising situation. “Street Scene” was considered very risqué in it’s time.

In 1932, Estelle appeared in an important Fox film, “Call Her Savage”, in support of the legendary “IT” girl, Clara Bow. Taylor’s career was winding down and she only made one more 1932 film; retiring until one screen appearance in the United Artists’ 1945 prestige film, “The Southerner.”

Estelle Taylor died of cancer in Los Angeles on April 15, 1958, at age 58. The New York Times, in their obituary in their April 16, 1958 edition, ran a glamour photo of Estelle, from her 1928 film “Lady Raffles”; and referred to her as: “Ex-wife of Jack Dempsey Played Supporting Roles in Hollywood Movies.” Her Times obituary, while mentioning several of her movies, was not at all flattering to her as an actress. Indeed, the Times mistakenly wrote that she had been married to Jack Dempsey when she had appeared with John Barrymore in the 1924 film “Don Juan”. She and Dempsey had not married until 1925.

The Chicago Tribune’s obituary, composed by their Seymour Korman, of their Chicago Tribune Press Service, was decidedly more favorable. Korman’s lead paragraph said: “Estelle Taylor, 58, glamorous star of the silent films and one time wife of Jack Dempsey, died today (April 15, 1958) of cancer.” Korman also mentioned that: “Miss Taylor came to Hollywood in the early 1920s, after success in a Broadway musical, “Come On, Charlie”, and her sultry beauty won her quick acclaim here.”

After her divorce from Dempsey in 1931, Taylor did not remarry until 1943. She married Paul Small, a Broadway producer; and they were divorced three years later, in 1946. Estelle Taylor achieved late fame of another sort, as founder and president of the California Pet Owners Protective League. At the time of her death, she was vice president of the Los Angeles City Animal Regulation Commission. “The city council adjourned today in respect to her memory.” Miss Taylor was childless. Surviving are her mother, a sister and a niece, all of Los Angeles.

Jack Dempsey died on May 31, 1983, at the age of eighty-seven. The man from whom he won the world heavyweight championship in 1919, Jess Willard. Died on December 15, 1968, also at age eighty-seven. These two world champions lived the longest, in terms of years, than any other world heavyweight champion, before or since.

“The most popular prize-fighter that ever lived, “famed writer Paul Gallico said, “was Jack Dempsey…nearly everyone in every walk of life seemed to love and admire Jack Dempsey. There was hardly any class to whose imagination he did not appeal. He was and still remains today (Gallico was writing this in 1938) in the minds of millions of people the perfect type of fighting man,”

Quite probably, Gallico’s sentiments would hold true today in the year 2000; at least in the thoughts of men, and women, in their seventies. As we get older the champions we watched and worshipped, tend to grow in prestige, stature and greatness; and the memory of them will never fade.

That was the legacy of Jack Dempsey; as the popularity of the many books about him testify. However, it is unfortunate that these books did not bear strict adherence to the truth; in regard to telling the real story of the February 13, 1917 fight in Murray, Utah, between Jack Dempsey and Fireman Jim Flynn.