NEVER UNDERESTIMATE A REFEREE

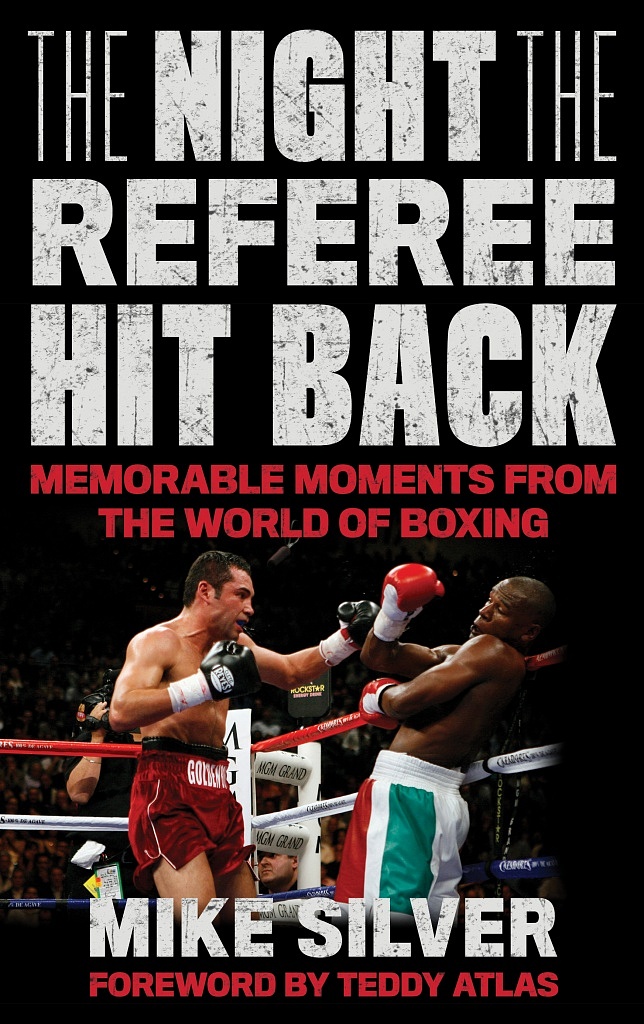

A review of Mike Silver’s The Night the Referee Hit Back

By Roger Zotti

Swing

The Night the Referee Hit Back: Memorable Moments from the World of Boxing, the title of award winning boxing historian Mike Silver’s latest book, refers to what happened on January 27, 1970, in Toronto, when a welterweight from Panama named Humberto Trottman, in round six of his fight against undefeated Clyde Gray, swung at 54-year-old referee Sammy Luftspring.

Apparently Mr. Trottman was dissatisfied with Mr. Luftspring’s officiating.

Ernest and Mike and Stillman’s

In Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (published posthumously in 1964), the author takes you to Paris in the 1920s, where you’ll visit the Tour D’Argent restaurant, Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company bookstore, and the Hole in the Wall bar, among other popular establishments.

Also, you’ll meet such literary luminaries as F. Scott Fitzgerald, his wife Zelda, Ezra Pound, Ford Maddox Ford, and Gertrude Stein.

Thanks to Hemingway’s writing artistry he puts you, the reader, there . . . in Paris . . . in those places . . . And with the aforementioned individuals who, when he writes about them, well, it’s as if they’re speaking not only to him but to you as well.

One of today’s most knowledgeable and trustworthy boxing writers, Silver, in his book’s marvelously and evocatively written autobiographical opening chapter, “Boxing in Olde New York: Unforgettable Stillman’s Gym,” does what Hemingway did when he wrote about Paris. But instead of Paris, Silver’s writing expertise places you, the reader, in Stillman’s 919 Eighth Avenue gym by evoking its smells: “ . . . a combination of liniment, stale cigar smoke, leather, and sweat.”

Its sights: “You could spend hours at Stillman’s just looking at the interesting faces of some of the characters who always showed up. I had never seen so many dented noses in one place. Half the guys standing around, whether fighters, trainers, or managers, had mugs that could have filled the cast of a Guys and Dolls production.”

And its sounds: “A cacophony. . . echoed through the gym: the rhythmic rat-a-tat-tat of the speed bags; jump ropes slapping against the hardwood floor; the thump of leather-covered fists hitting the heavy bags, and, if hit hard enough, the jangling sound of the chains that bolted them to the ceiling; fighters snorting and grunting as they shadowboxed and threw punches at imaginary opponents.”

For Silver, “Walking into Stillman’s was like entering a time warp,” Silver writes. “I felt like I had suddenly found myself in an old black-and-white movie. All my senses were engaged in taking it all in.”

It isn’t an exaggeration to say Silver’s education in the sweet science began at Stillman’s. As he puts it, he has never forgotten its “magic and allure. I thank my lucky stars I was able to experience it,” a statement echoing Hemingway’s remark that “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you. . . . ”

Tiger Ted

Silver’s superbly written book is a compilation of twenty-eight articles he wrote and interviews he conducted over the past forty years.

One of his interviews—and I’m a SUCKER for interviews with athletes (especially boxers) and actors— is with his friend Tiger Ted Lowry, who grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, and graduated from Troup Junior High School, which has a personal meaning for me and a friend, Stu Rosen of South Windsor.

In 2008, we met Lowry at the Connecticut Boxing Hall of Fame Induction ceremony, at Mohegan Sun Casino in Uncasville, CT. He was one of the year’s inductees. It was a reunion of sorts. Stu and I, you see, were also graduates of TJH many years after Lowry’s class graduated. That Lowry was a Troup alumnus was a pleasant surprise and, yes, we chatted about the school and in specific about its enormous playground, where there were usually several softball games taking place during and after school hours.

Lowry fought from 1939 to 1955 and compiled an interesting record of 70-68-10 (35 K0s.) Wait! Sixty-eight losses? “Ted lost count of the number of hometown decisions that went against him,” Silver explains. “At least half of those 68 losses could just as well have gone the other way. He took those losses in stride and accepted them as the cost of keeping busy and earning a steady income.”

But it was a different matter when Lowry went up against “a top contender,” Silver writes, “and he had nothing to lose and everything to gain . . . he became what he always could have become and let loose with the full measure of his talent.”

Two examples: In his 1948 fight against the great Archie Moore, he gave the Old Mongoose fits for ten rounds, though he lost the decision. Later Moore admitted Lowry was one tough, savvy hombre!

Then there was Lowry’s 1952 fight against light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim. “Maxim was scheduled to defend his title against the great Sugar Ray Robinson,” Silver writes. “There was no way the powers in charge would let allow Ted Lowry to get the decision and put a damper on that big fight.”

In his interview with Lowry, Silver asked him how Muhammad Ali would’ve fared against the great Joe Louis. “I think Joe Louis would have knocked him out,” Lowry said. “Joe was the type who stayed right on you and it would be hard for Ali to outbox him, and if Joe hit him . . . it would be terrible. Joe did not back up. He was always dangerous with the left hand or right hand, it made no difference.”

Asked by Silver if he thought “Muhammad Ali was a great fighter,” Lowry said, “No. He moved too much for me. But he was a good boxer. Good boxer. But I don’t think that at the time he was fighting, the top-notch fighters were around.”

Also, Silver interviewed the great former light heavyweight champion Archie Moore. Asked who he thought was the greatest pound-for-pound boxer he ever saw, Moore pondered the question for “about ten seconds,” Silver writes, then said, “Henry Armstrong. Here is a man who won the featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight titles all in the same year, and the men he beat to win those titles were great fighters in their own right.”

Carlos Ortiz, one of the best lightweight champions ever, was asked, in his interview with Silver, what he thought “was missing from today’s fighters compared to those of your generation?”

Ortiz, who fought from 1955 to 1972, was the WBA lightweight champion from 1962 to 1965 and from 1965 to 1968. He compiled a 61-7-1 (30 KOs/1 KO’by) record. “The good fighters don’t want to fight the good fighters,” he told Silver. “Champions don’t want to fight champions. . . . if you want to be number one you’ve got to be number one all over. . . . In the second place, who’s champion today? There are so many champions. . . . And there are so many weight divisions. . . . In my time there was a pride of being champion—one champion of everybody.”

Sammy and Humberto

Rewind to the incident between Humberto Trottman and Sammy Luftspring. What Trotman didn’t know was that the Canadian-born Luftspring was a former amateur and professional prizefighter.

A competitive welterweight, Luftspring won 23 of 27 fights from 1936 to 1938. One of those victories, a thirteen-round knockout of Frankie Genovese, earned him the Canadian welterweight championship.

In Silver’s June 11, 2014, article about the Trottman-Luftspring incident he quotes Luftspring, who, in his 1975 autobiography Call Me Sammy, writes: “What was going on in my head was that I was in a boxing ring with a boxer who had just thrown one punch and probably intended to give me a sample of a few more. How I ever managed, purely by instinct, to dodge his right I will never know. But I had no intention of letting it be unreturned. . . . And the next thing I knew, I had popped him three or four more times without getting touched again myself.”

When Luftspring moved to New York City in 1939, Silver points out, “Al Weill became his manager and Whitey Bimstein his trainer.” He retired in 1940 with a 31-8 (13KOs) record and in 1985 was inducted into the Canadian Boxing Hall of Fame.

~~

Likehis two other books, The Arc of Boxing: The Rise and Decline of the Sweet Science and Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing, Mike Silver, in The Night the Referee Hit Back, has again created a skillful and fast-paced book about boxing, one full of sharp, perceptive writing about how the sport was, is, and probably will be.

The author of two books about boxing, Friday Night World and The Proper Pugilist, Roger Zotti is a regular contributor to the IBRO Journal. He can be reached at rogerzotti@aol.com for more information about his books.