THE SWEET SCIENCE IN THE NUTMEG STATE

A review by Roger Zotti of Mark Allen Baker’s Connecticut Boxing

. . . how deeply appreciative I am to everyone who enjoys my work. I want readers to know how dedicated I am to each work and how much it means to me to be able to write about the sport we love.

Mark Allen Baker

1

I’m beginning this review/appreciation of Mark Allen Baker’s latest book, the informative, satisfying, and meticulously researched Connecticut Boxing: The Fights, The Fighters and the Fight Game (History Press), on a personal note. Personal because it involves Gaspar Ortega, whom I’ve met several times at various Connecticut Boxing Hall of Fame induction ceremonies.

In chapter seven, “El Indigo,” we learn Ortega was born in Mexicali, Mexico, in 1931, turned professional in 1953, and settled in New York in 1954. “If he was serious about the ring, which he was, there was no better place to forge a career than the ‘City,’” Baker writes.

He later moved to Connecticut, spending the majority of his life in the Nutmeg state.

When he retired from boxing in 1965, he had assembled a record of 131-39-6. Among his opponents were Kid Gavilan, Carmen Basilio, Nino Benvenuti, Emile Griffith, Benny Paret, Ralph Dupas, Don Jordan, Issac Logart, Hardy Smallwood, and Florentino Fernandez. (At one CBHOF Induction ceremony I asked him who was the hardest puncher he ever faced, and without pausing he said it was Fernandez.)

Along with Ralph “Tiger” Jones and Gavilan, Ortega appeared on national television more often than any other fighter of that era.

And then there was former welterweight champ Tony DeMarco. He and Ortega fought three times. Each fight was memorable. In their first encounter, at Madison Square Garden in 1956, Ortega wasn’t fazed by the odds, which were 5-1 in against him, and at the end of ten action filled rounds he had earned the decision.

Rematch a month later! Again at the Garden. Again Ortega was awarded the decision. Boston Garden was where their third encounter took place early in 1957, and this time DeMarco was awarded the decision.

Baker writes, “[Ortega] left nothing on the table during his long career in the ring, as they say. Nothing. Gaspar Ortega was a ring legend. In 1968, he moved his wife and four children to Connecticut. Heavily involved with the East Haven community, he has always been beloved and respected by everyone he comes into contact with. In a testament to his skills as a father, his son Mike Ortega became a world-class boxing referee.”

In addition to Ortega, who was inducted into the Connecticut Boxing Hall of Fame in 2006, Baker writes about seven other fighters from Connecticut, among them Marlon Starling and Willie Pep.

In the chapter titled “The Magnificent,” we learn that Starling compiled a stunning 97-13 record as an amateur. He retired in 1990 with a record of 45-6-1.

In “The Fights, the Fighters and the Fight Game” chapter, Baker writes that Starling, who turned professional in 1979, “was precisely what professional boxing in Connecticut needed at this juncture [1980-89]: an unstoppable, charming, and talented welterweight.” Citing several of Starling’s career highlights, Baker continues: “[He] lost a fifteen-round decision to WBA/IBF welterweight Donald Curry on February 4, 1984”; three years later he scored an eleventh round TKO over Mark Breland “to win the WBA welterweight title”; and in 1989 he stopped England’s Lloyd Honeyghan in round nine “to win the lineal/WBC welterweight title.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that Starling would give any of today’s top welterweights fits with his ring savvy . . .

Inducted into the CBHOF in 2005, Starling is, like Ortega, a friendly and personable presence at the yearly Hall of ceremonies.

In the chapter about Willie Pep, who was born Guglielmo Papaleo, nicknamed “Will-o’-the-Wisp,” and was the world featherweight champion during most of the nineteen-forties, Baker writes about Pep’s 1946 non-title fight against Jackie Graves in Minneapolis: “Constantly in motion, Pep, weaving, bobbing, dodging and dancing, won [the third round] without landing a single solid punch. (He did admit to casting a few light jabs.) Impressing the judges solely with his ring prowess, Pep was masterful . . . For the record, Pep won the fight via knockout in the eighth round.”

Boxing fans know that if you name just one of Pep’s opponents, well, you must also mention the great Sandy Saddler because, as Baker writes, “the duet [are] forever linked in ring lore.”

Their first fight was in 1948 and Pep, who had held the featherweight title for six years, was stopped in round four. In their rematch on February 11, 1949, Pep regained his title by decisioning Saddler in fifteen rounds. For W.C. Heinz, in Once They Heard the Cheers, “. . . the second Saddler fight was the greatest boxing exhibition I ever saw . . . . it was Willie’s fight from the first round on when he jabbed Saddler thirty-seven times in succession without a return.”

In 1950 they met for the third time, and Saddler scored an eighth round knockout. Then, at the Polo Grounds in New York, in 1951, they battled for the fourth and final time, with Saddler stopping Pep in round nine, a fight that, Baker writes, “by many accounts [was] one of the dirtiest contests ever fought in a boxing ring.”

Pep retired in 1966 with—and brace yourself—a 230-11-1 (65 KOs) record. In 2005, he was inducted into the CBHOF

Two of the greatest featherweights ever to lace on the leather mittens, Pep and Saddler, who compiled a 144-16-2 (103 KOs) record during his twelve year career (1944-56), were elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

2

Baker covers ten Connecticut boxing venues in depth, including the fabled New Haven Arena. I say fabled because if you’re from the Elm City and enjoyed sports and other kinds of entertainment, the Arena became part of your life: It was where you could watch basketball (pro, college, and high school), hockey (the New Haven Ramblers of the American Hockey League and later the New Haven Blades of the Eastern Hockey League), the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey circuses, the Ice Follies and the Ice Capades, wrestling, concerts, symphonies, roller derby—any fans of all-stars Joan Weston, Margie Laszlo, or Ann Calvello out there?—and of course boxing.

Too, Baker lists many of the fighters who appeared at the Arena, including the great Sugar Ray Robinson, who in 1956 fought journeyman Bob Provizzi. So three friends and I were there to see boxing royalty in person.

Following the Provizzi fight—which Robinson won by decision—in January 1957 he fought and lost to middleweight champion Gene Fullmer at Madison Square Garden. But in their rematch four months later, at the Chicago Stadium, Robinson’s perfect left hook knocked out Fullmer in the 5th round to win the middleweight title.

3

Fan or not of the sweet science, you’ll be rewarded by reading Connecticut Boxing and Baker’s other works as well. He’s written twenty-three books, seven about boxing, and in them you’re always given important historical background information—clearly and precisely written—about the individuals, time, and places his books cover.

A book to cherish, Connecticut Boxingis available at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and various outlets in Connecticut.

The Interview

In a recent interview with Baker, I asked him four questions about Connecticut Boxing, the first being . . .

. . . what prompted you to write your latest work?

MAB: The rich history of Connecticut boxing has been overlooked, at least in my view, for years. Recognizing the need to address the issue, I believed a title such as Connecticut Boxing: The Fights, The Fighters and The Fight Game would be a great place to begin.

RZ: Most challenging about writing it was . . . and why?

MAB: Well, with an impressive history, it was clear from the start of the project that space was going to be an issue. Limited to 50,000 words, and 50 images, I mapped out in my mind the things I wanted to cover. The pillars of Connecticut boxing—Battalino, Delaney, (Johnny) Duke, Kaplan, Ortega, Pep, Starling and Tunney—were used to tell aspects of the story. For example, I used Jack Delaney and Lou Bogash to illustrate regional (Bridgeport) rivalries, and I used Marlon Starling as an example of a homegrown fighter who made the successful jump from amateur to professional ranks.

Analyzing Connecticut boxing markets and noting historical venues, led to the great fighters and fights, along with those contributors outside the ropes.

The next jump was to Casino Boxing, an important element of Connecticut boxing history. Stepping outside my comfort zone, I noted the “Top Twenty-Five Boxing Matches in Foxwood History” and the “Top Twenty Boxing Matches in Mohegan Sun History.” And finished with a chapter about the Connecticut Boxing Hall of Fame.

RZ: What do you hope readers take from Connecticut Boxing?

MAB: One thing: An appreciation for the rich history of Connecticut boxing. The big names always surface like Battalino, Bogash, Delaney, (Johnny) Duke, Kaplan, Ortega, Pep, Rosenbloom, Starling and Tunney, but too many others, including those around the sport, fall through the cracks. The best part of being a writer is discovering individuals who have for some reason or another, been overlooked. Then, bringing them back into the forefront.

Connecticut has many contributors, in and around the fight game, that don’t get enough recognition for their achievements. The beloved Julio Gallucci, aka Johnny Duke, is a good example. A wonderful instructor, and mentor to many, who operated the Bellevue Square Boys Club in Hartford. He touched the souls of many in the Connecticut fight game. And folks can read about it in this book.

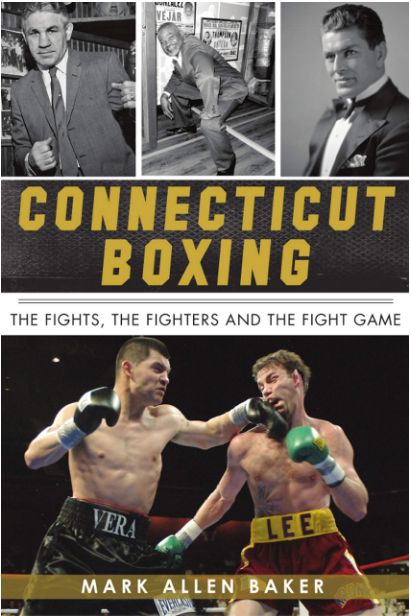

RZ: Anything else you’d like readers to know about you and/or your book, which, by the way, is enhanced by many images of boxers and boxing venues?

MAB: My apologies for a couple oversights that slipped through the production process. They will be corrected in subsequent editions. I would also like to thank Glenn Feldman, Rick Kaletsky and Emily Harney for their contributions.

I have a biography about Lou Ambers that was recently published by McFarland. When you think of great lightweight boxers of the past, he has been a name that has been overlooked by historians. Yet, he was a deeply religious and talented professional athlete who overcame many adversities including the tragic death of a ring opponent (Tony Scarpati). It is an inspiring story that boxing fans will enjoy.

A regular contributor to the IBRO Journal, Roger Zotti has authored two books about boxing, Friday Night World and The Proper Pugilist. His most recent book is Jack Kerouac and the Whiz Kids. Contact him at rogerzotti@aol.com for more information about his writings.